Précis/TL;DR: in which we discuss some of the important ways the Interwar Era in Europe has very little to do with much of the ‘democratic backsliding’ debate going on today. A short list of new publications rounds out the post as always.

This newsletter is an expanded version of a Twitter thread I made recently, prompted by the ongoing, high-pitched debates over authoritarianism in the Western world. Naturally, many of these discussions center around the upcoming US presidential election. But they also bleed into the broader debate over ‘democratic backsliding’ in Europe, Latin America, and elsewhere in the world.

This is not an election essay, but rather an intervention into a wider discussion relevant to social scientific, historical, and commentary arguments that sometimes get more confused than is helpful - or accurate.

Autocratization Now and Then

A key part of the ongoing autocratization debate centers on how authoritarian regimes come to be. That is, what is their origin, how do nascent authoritarian leaders capture power, and ultimately how do they maintain them. This is pertinent, as a major analytic thread pulled by many contemporary scholars is that the means and methods for autocratization have changed in the 21st century.

There is, in some views, a new ‘autocrat’s toolkit’ operating in the modern age. Rather than coups or violent overthrows, many argue that today authoritarianism comes primarily in the form of gradual transformation through the capture of institutions and success in multiparty elections - using examples such as Hungary, Turkey, or Russia to make the case.

I have written on this before, and it is an ongoing area of research in my own scholarship. I think there is certainly merit to focusing on more gradual transitions to authoritarian rule (especially for European and certain post-Soviet and Latin American cases - although often not others, as the new ‘coup belt’ in West Africa attests).

In any event, there remains wide regional variation and greater case heterogeneity across examples of modern autocratization than some more popular writers seem to allow. It is also not necessarily as easy as one might think. That is a discussion for another time, but you can find an article of mine from two years ago that lays out some of the difficulty with actually building stable authoritarian regimes (and in reference to the particular case of the US).

However, for all the discussion of gradual transitions, I also have noticed there is a kind of cognitive dissonance in a decent amount of the public discussion. At the same time that many argue we need to be vigilant against ‘democratic backsliding’ and the gradual dismantling of democratic regimes through institutions, the same people also regularly find recourse to the historical period known as the Interwar Era (the 1920s-1930s) as a primary locus for political analogies.

This is understandable (and interesting in its own right), but it is not especially applicable to a framework privileging ‘backsliding’ itself, or a deceptively innocent drift into authoritarianism. The Interwar Era really is quite different in this sense.

My prompting to think about this came from one of the many historians who have been prominent in the continuing modern authoritarianism debate (he shall remain anonymous here). He suggested that ‘what we learned from WWII is that people go along with authoritarianism.’ The sentiment is correct in a general sense. People absolutely do ‘go along’ with authoritarian rule all the time.

But what is not correct is assigning a ‘people are ok if authoritarianism happens’ vibe to the Interwar Era itself. It was very much so the opposite. People at the time certainly didn’t just ‘let it happen,’ nor was the period one that can be characterized by complacency.

Complacency is not the word to describe the existentially polarized and very violent European Interwar. It’s simply the wrong place to discuss this kind of backsliding or soft autocratization dynamic implied by a ‘go along with’ framework. The reality is much more forceful, violent, and in many ways more disturbing for the modern democratic mind.

We can treat this quickly in just a few points. Authoritarian regimes in the Interwar Era arose for three big reasons:

the coercive imposition of authoritarian rule after victory in a bloody civil war;

the hopeless fragmentation of and frustration with parliamentary democracy among national elites across many countries; and

activists, social movements, and politicians who actively sought to end democracy, and did so in the name of ending it and replacing it with explicit authoritarian governance.

Civil War and the Threat of Communism

First, on the issue of violent imposition. We sometimes forget that the Interwar Era was kicked off by communist victory and the imposition of an innovatively brutal authoritarian regime in Russia with the end of the Russian Civil War. This, in turn, dovetailed with major communist and authoritarian socialist revolts in Hungary, Bavaria, Finland, and Italy in the late 1910s and early 1920s.

Authoritarianism therefore was imposed at the barrel of a civil war gun in the (soon-to-be) Soviet Union and attempted elsewhere. And the USSR made a very serious effort to conquer Poland in 1919-1920, which just underlined the point that communism was an active, present, and extremely real threat. Communism was the first driver of authoritarianism in Europe, as well as the origination point for the sustained perception that it was coming to overthrow democratic or previously existing governments everywhere. Because it was.

Indeed, the great German academic Ernst Nolte argues that fascism and the broader Interwar authoritarian revanche was fundamentally a reaction to communist threat. And that it could be understood - somewhat metaphorically - as a ‘European Civil War.’ You can find translations of his work online, I highly recommend them.

So that is the first point. It was not blasé complacency. It was the Bolsheviks murdering their way to victory in the Russian Civil War, crafting a new and brutal form of authoritarian rule from the carcass of the dead Russian Empire, and then credibly threatening invasion to expand communism further. All while authoritarian communist statelets were attempting to seize power amid general civic disorder in various parts of Europe.

Of course, in the long run, the USSR’s success in the earliest years of the Interwar would ultimately doom half of Europe to an especially repressive form of institutionalized authoritarian rule until 1989. Although the working out of that tale also involves Soviet-Nazi collusion and the post-WWII settlement. Communism was ultimately the primary generator of authoritarianism in much of Europe for the last century, although not the only one.

Fragmentation and the Delegitimation of Parliamentarism

The second way authoritarianism comes to Europe in the Interwar is also not a situation of ‘people just were ok with it,’ but rather the active failure of democracies during the period to sustain internal stability. This failure convinced elites to throw democracy away.

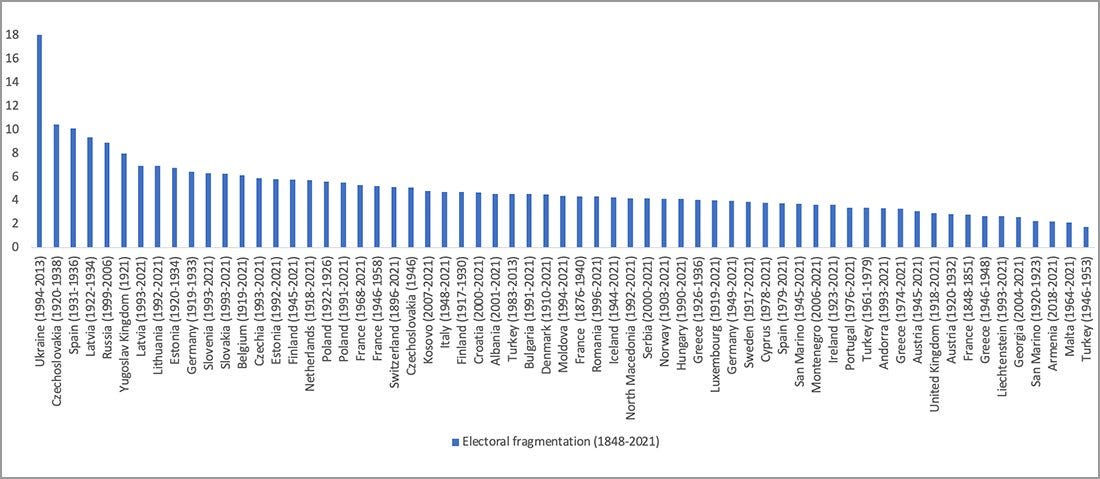

The democratic republics in the formerly imperial East and the constitutional monarchies in the Mediterranean and the Balkans especially tended towards fragmented parliaments, rotating coalitions, & short-tenure PMs. Poland, Yugoslavia, Italy, Spain, Germany, and more all had this problem. You can see one way to measure this in the chart below, although there are many others.

Specialists nuance this - for example, the idea that greater political fragmentation mostly leads to breakdown is not always found outside the period. Nevertheless, politicians, constitutional monarchs, military elites, and scholars at the time all cited parliamentary fragmentation/indecision as very bad. Key academics at the time, such as Max Weber, Hermann Heller, and Carl Schmitt all wrote on this extensively, and it was a major theme in speeches by party leaders across the period. Many would argue that the complexity of modernity itself meant that parliamentary government was incompatible with development and stability.

Ultimately, the phenomenon of persistent fragmentation (and the perceived inability to reform away from it) would provide legitimacy to the idea that democracy had failed - one which many political elites took firmly to heart. This would lead to coups in a large set of countries. Just in the 1920s we get: Piłsudski (Poland), Primo de Rivera (Spain), Smetona (Lithuania), Bulgaria (Tsankov et al), and of course Italy (Mussolini).

Many of these coups and self-coups would be justified by the failures of parliamentarism as practiced during the period, the shifting coalitions leading to perpetual indecision, and the sense that the state itself was under threat from persistent political instability in legislatures and in the halls of government. Thus a common pattern of politically-justified emergency authoritarian rule - which would then be extended far longer than some elites may have initially realized - was legitimized by a sense of democracy’s failure as a system itself.

Substantive Visions of Authoritarianism

Which brings us to the related point number three. One major reason for democratic failure was the delegitimation of parliamentary government. As noted above, this often led to coups to ‘cut the Gordian knot’ and install a kind of emergency rule. But the other component to this phenomenon was that many actors at the time had an active interest in authoritarianism.

Some of the coups would only be justified by exigency or failure, especially in the earlier days of the Interwar Era. But by the 30s, ideas working out how to modernize/develop the state through authoritarianism would be more fleshed out. The campaign to make German President Hindenburg a permanent ‘protector of the nation’ and some of the intellectual work around so-called “authoritarian liberalism” are just two famous examples in the years immediately prior to Hitler’s rise to power.

But authoritarianism as a positive governance ideal had far broader appeal. This would include attempts at detailing authoritarian political corporatism in Mussolini's Italy and Salazar's Portugal, as well as later efforts in Austria, Spain, Germany, Greece, and elsewhere. These cases are all emblematic of this more intentional thinking about authoritarianism as a substantive good - not an emergency measure to overcome crisis, but an outcome in itself.

Indeed, the Austrian Ständestaat, the Päts government of Estonia, the early years of the Franquist regime in Spain, the two proper fascist states, and others would think increasingly institutionally, claiming to build something more than a strongman regime for its own sake. They were creating what I’ve called in ongoing scholarly work ‘institutional-hierarchical’ authoritarian regimes, and viewed them as solutions for the long term.

The means and methods were diverse. Many of these regimes attempted to build out ‘movement-parties,’ which would survive in Communist Europe even as WWII destroyed them elsewhere. Some of them were actually created to stop more radical fascist movements from gaining power (with successes in Estonia and Austria most notably, and a very consequential failure in Germany). This is neither a lesson about passivity, nor complacency. But rather a very different explicit and intentional shift towards authoritarianism happening during the era - one which would have continued ramifications for authoritarian regimes elsewhere in the world into the 1960s.

Lessons Not to Learn from the Interwar

By 1938 there were just very few democracies left in Europe. But in almost no case did people just vaguely ‘let it happen’ and be fine. The rise of authoritarianism in the Interwar Era was due to violent coercion, due to the perceived clear failure of democracy, and due to popular circulation of ideas of alternative authoritarian governance.

As a coda to this discussion, where you do get ‘let it happen’ vibes is really only during the period after conquest. In France, the Nordics, in East-Central Europe (Czechoslovakia, for example), and Balkan kingdoms we see this. But those regimes were imposed from without or negotiated in a context of overwhelming force, mostly by Nazi Germany and then later by the Soviet Union. This reality is very far from the current debate, however.

All of this is to say that the Interwar Era is not the right place to look for a tale of gradual, complacent de-democratization. It is a time of civil war, political violence, coups, elite and institutional delegitimation, and widespread positive visions of authoritarianism. There’s no reason we cannot look to the Interwar for lessons on authoritarianism today, but we have to be careful when we apply one framework and use another one as our primary analogy.

Further Reading & Listening

There are a few new publications worth mentioning since our last newsletter:

First, a new essay with my coauthor Dima Kortukov on patriotic education, official ideology, and multimedia illiberalism in wartime Russia. It is an outgrowth of our academic article on the subject (linked below). Read “‘The DNA of Russia’: Ideology and Patriotic Education in Wartime Russia” here.

Second, a plug for my new article in RIDDLE Russia on the institutions that undergird and complicate Russia’s wartime dictatorship and the future post-Putin succession. I provide an overview of the complicated and layered state institutions, political entities, and other politically-relevant bastions within Russia’s authoritarian regime. Read “The Institutional Ecosystem of Russia’s Personalist Dictatorship” here.

Third, a new academic article written with my friend and coauthor Dima Kortukov on developments in official ideology within Russia today and newly published in Communist and Post-Communist Studies. Read “The Foundations of Russian Statehood: The Pentabasis, National History, and Civic Values in Wartime Russia” here.

Fourth, a new CNA paper written by myself and my excellent colleague Dmitry Gorenburg on Russia’s General Staff. This project is a concise primer on the key command and operational-strategic institution in the Russian Armed Forces, and was sponsored by U.S. European Command’s Russia Strategic Initiative and given the green light for public release last month. Read The Central Brain of the Russian Armed Forces: The Modern Russian General Staff in Institutional Context here.

Finally, for those who missed recent previous newsletters, here is one where I detail a new course I’ll be teaching in the coming Spring 2025 semester:

Outside Reading Corner

I’m introducing a new section to this newsletter. Here I’ll highlight books I’m reading or excited about, and therefore recommend. Just one entry today: The Evolution of Authoritarianism and Contentious Action in Russia by my colleague Bogdan Mamaev. Here is the blurb for the book, published open-access at Cambridge University Press:

This Element examines the evolution of authoritarianism in Russia from 2011 to 2023, focusing on its impact on contentious action. It argues that the primary determinant of contention, at both federal and regional levels, is authoritarian innovation characterized by reactive and proactive repression. Drawing on Russian legislation, reports from human rights organizations, media coverage, and a novel dataset of contentious events created from user-generated reports on Twitter using computational techniques, the Element contributes to the understanding of contentious politics in authoritarian regimes, underscoring the role of authoritarianism and its innovative responses in shaping contentious action.

It’s a short book, mostly for specialists, but if you are interested you can find it cheaply here.

-Julian

Re: your RIDDLE Russia article. I think you are a bit overestimating the role of institutions over the informal networks, but that’s understandable since they are on the surface and their activities are visible to an outside observer, while all the informal stuff is essentially closed to all non-participants and most attempts to understand it boil down to tea leaf reading. Still an informative piece, though.