Précis, aka TL;DR: in which we begin a discussion of the academic concept of ‘illiberalism,’ where it came from, and what it means. In doing so, a detailed background note on how I became interested in all of these developments sets the stage, before an initial foray into how and why it matters (we think). As always, the concluding section includes recent publications and working papers.

A Backgrounder

This essay begins with some personal background. In a somewhat unintended development, over the last several years I have become a subject-matter expert on the academic concept of ‘illiberalism’ and many of its particular, ideological expressions in both Eastern Europe and the English-speaking world. This was not intentional, as my academic background really has two points of core focus: 1) authoritarian regimes and the political institutions within them in general, and 2) the politics of Russia, Ukraine, and the broader post-Soviet space specifically.

And those were the dominant threads that ran through my academic training, not ideologies or ideas. My Ph.D dissertation was on parliamentary and council institutions in the electoral authoritarian regimes of Eurasia, and my formal course of study to get there involved a lot of classes and reading on political regimes, party politics, state institutions, repression and protest, and so on - that which makes up the small, but mainstream ‘comparative authoritarianism’ corner of the discipline.

This research field, in turn, comes not from political theory or the history of ideas, but takes a very empirical, institutionalist approach sitting firmly within the comparative politics subfield of political science. Meanwhile, my day job is as a research analyst on national-security and military-political issues related to Russia and Eurasia. And I teach a straightforward Russian Politics course for undergrads on the side at GWU. None of that deals with the clunky term ‘illiberalism’ directly, in principle.

Nevertheless, at least in peer-reviewed and related scholarly settings, I’ve written as much, if not more, on contemporary ideological developments dealing with the concept of ‘illiberalism’ as I have anything else. How did this happen?

It all started with Russia. While researching parliamentary lawmaking in the Russian State Duma in the mid-2010s, I noticed that some of the most interesting - and controversial - legislative outputs of that authoritarian legislature after 2011 involved what we could term ‘moral-cultural’ issues. These included laws providing formal legal protections for the “feelings of religious believers,” restricting adoption from the United States, and banning “homosexual propaganda,” among several others bills and laws of interest.

Many of these laws, rather than being fully directed from above in the Kremlin, were shaped substantively in parliamentary proceedings and committee deliberations, and had been initially developed through policymaking experiments at the subnational level in years prior. Which makes for a nice puzzle for an authoritarianism scholar to explore for those reasons alone. But they also all shared an ideological similarity based in a kind of cultural conservatism and aggressive reaction against ‘liberal’ norms promoted in the West - which as we shall see forms the core of the disputed and ugly-sounding concept of ‘illiberalism.’

I’ve had one article published from this initial research directly, looking at how the “homosexual propaganda” bill had been developed in Russia, and then following its diffusion across parts of the post-Soviet space. I’d written it several years ago now, although it’s just fully published this summer (thanks to happy academic timelines, as always). The article formed the basis of a core dissertation chapter, as well. But this research process also had me thinking about these sorts of ‘illiberal’ legislative projects in general, and what they meant for Russian politics. So, I’ve continued to mull on this over time.

Two years ago, I would publish another separate article trying to make sense of where this kind of policy and cultural illiberalism was coming from in Russia overall. I found that it was far more complicated than a simple story of the Kremlin masterminding a cultural policy for purely instrumental reasons (i.e., that they did this just to maintain control over society). Rather, important meso-level institutions such as the Russian media ecosystem, the parliament, the Russian Orthodox Church, and other places also acted as active and dynamic sources of ideological creativity and production that were distinct, if certainly in general agreement with, managers in the Kremlin itself.

In pursuing this latter side-project, I began working extensively with Dr. Marlene Laruelle. She is one of the foremost experts on Russian nationalism, conservative politics, and esoteric ideologies (e.g., Dugin), and had just started a major project on the illiberalism concept itself. Without speaking for her, it’s fair to say that one of her motivations was to assess exactly what this term meant in scholarship, as it had become widely, but confusingly, used to describe many changing elements to European and Eurasian politics over the last two decades. She was able to get funds to support a new Illiberalism Studies Program at GWU, with which I am affiliated, to study the topic more systematically and provide a platform for wide-ranging scholarly research. And she has written directly on a core conceptual question in this growing field: what is illiberalism itself?

This interest in illiberalism as a concept (is it useful? what does it describe? how is it different from other in-vogue concepts like ‘populism’? is it just ‘conservatism’? how is different from all these other ways to talk about politics? what is its relationship to authoritarianism and authoritarian regimes? etc) made me continue to think more broadly on the topic, and explicitly beyond just the Russian case.

And this dovetailed with a growing personal interest in the new ideologies and alternative worldviews that I was noticing crop up on the American side of things, especially through social media after 2018 or so. So that’s how I ended up writing papers looking at some of the more esoteric ideological developments among English-speaking writers in the US and the UK. These all fit under the general label of illiberalism, as both Marlene and I were now thinking about it, but in distinct and surprising ways (at least for me). In doing so, a research agenda that started in my usual Russia bailiwick has over time brought new and very different points of interest into focus.

These topic areas are in many ways quite far afield from Russian legislative politics. For example, I’ve now published multiple articles looking at the rather esoteric ideology known as ‘Catholic integralism,’ which grew from a truly marginal position in one tiny corner of the English-language internet into a phenomenon that was being widely written up in mainstream policy and commentary journals at the end of the 2010s. For whatever reason, between the mid-2010s and 2021, integralism went from a blogosphere curiosity to the pages of The Atlantic and the New York Times. And it remains afforded a prominent place as a boogeyman in discussions on ideological changes within the American Right since the Trump election. So I’ve tried to apply conceptual insights and a comparative social scientific approach to this development, which has in turn led me down ever further interesting roads.

Integralism remains marginal in its fullest expression (and I expect it to continue as such, more or less). Yet here in the US and other Anglophone countries, the critical core of that ideology has been molded and partially transformed into a broader debate surrounding a new term: ‘postliberalism.’ This is a much more amorphous word, but has become something of a shorthand for illiberal politics often with a traditionalist/religious/reactionary-communitarian inflection specific to the US and the UK. My own claim is that what practitioners call postliberalism is exactly that, a recognizable version of illiberalism specific to our sociocultural space, shaped by our particular ideological environment, historical conditions, and political institutions.

You can see for yourself, of course. Recent books published this summer by Patrick Deneen, Mary Harrington, Sohrab Ahmari, and Christopher Rufo, for example, are all either explicitly or implicitly categorizable as sitting within this shifting ‘postliberal’ intellectual ecosystem. And I’ve suggested that we can productively compare nascent postliberal thought in the Anglo-American world with the much more successful brand of illiberal politics found in Eastern Europe, although with important caveats and differences.

But that’s not all. I’ve also delved into other curious features of the current era, such as the growing prominence of ‘authoritarian theorists’ such as Curtis Yarvin or Charles Haywood in internet-based, American right-wing thought, the rise of Caesarist characterizations of politics, and amorphous ‘dissident’ intellectual groups involved in sometimes-overlapping debates that have been simultaneously seeping into elite discussions as well. I’ve also taken on the question of whether - and how - an authoritarian regime might emerge in the United States.

Naturally, I’ve been drawn to research on all of these as they touch on my primary academic interest in authoritarianism itself, of course. In fact, in important ways the ultimate motivation for me in this space has been trying to figure out exactly what elements of these contemporary ideological dynamics can be plausibly coded as authoritarian, or influenced by historical authoritarian regimes, or promoting a future authoritarianism in a serious way… and what are simply something else. Frankly, that’s why I bothered to dive into integralism, for example, as I was trying to figure out exactly whether it was ‘fascist’ or not, as some magazines had suggested. I’ve come to some conclusions on that and other ideologies/actors in this area, but there’s plenty of uncertainty remaining.

At present, I now have three different papers (two peer-reviewed articles and one accepted book chapter) on the conceptual relation between illiberalism and authoritarianism from different scholarly perspectives and how we should define them, two pieces on integralism (one published essay and another forthcoming book chapter), two more on ‘authoritarian theorists’ (one article under final review and one summary paper for a policy magazine), two on the prospect of authoritarianism in the US case (one article and one summary piece), and several more comparing illiberalism in the US/UK with that in Eastern Europe (one academic article under review and two smaller papers).

With all this either out or in the process of publication, I hope to be done with the concept work (as well as most of the descriptive analysis), for the time being. At this point, I probably have enough material for a book or two, which I think might be a task I’ll have the bandwidth to take on two or three years from now. This was certainly not the plan when I began the Ph.D many years ago, and it’s also definitely not my day-to-day professional work.

Nevertheless, I’m quite convinced this scholarship is relevant, and speaks to many conversations and research agendas both in and outside of academia - and on issues that many academics really have little to no visibility on in the first place. On a few of these topics, my work constitutes perhaps one fifth (or more) of the total published academic literature as of summer 2023. For others, it is a drop in a larger bucket of growing scholarship, but which speak to major, ongoing debates. The enterprising reader is of course welcome to reach out and pick my brain on all these issues, as they remain areas of genuine sustained interest.

So, what is all of this about really?

The Dawning of Illiberalism Studies

A core motivation for working in the field of illiberalism studies (for me, and for a significant group of other scholars as well) is trying to assess what sociopolitical phenomenon the growing academic literature is exactly capturing. That is, what do we mean when we call something ‘illiberal,’ and why does this add any analytic value? What does it entail? What makes it different? Why should we even care? This may seem silly to outside readers, but it reflects the curious way in which the field has developed over the last twenty+ years.

In brief, the term ‘illiberal’ was first used as a way to describe new, post-Cold War democracies around the world that did not look the way scholars expected or had hoped. Initially, this was in reference to core questions such as the fairness of elections and rights in general - in other words, questions about regime-type. So we applied a term, ‘illiberal democracy,’ which meant something like 1990s democracies that did not follow the assumed course of institutionalized civil liberties, ‘liberal’ human rights, Western-style elite consensus, fully peaceful elections, and so on. This quickly turned into a separate debate about authoritarianism, in which illiberal democracy was reconceptualized as ‘electoral authoritarianism’ (also known as a ‘hybrid regime,’ ‘semi-democracy,’ ‘semi-authoritarianism,’ ‘pseudo-autocracy,’ or ‘competitive authoritarianism,’ among others).

As this academic debate ground on, ‘illiberal democracy’ itself was quickly dropped in favor of adding a new category type to our schemas of authoritarian regimes, a classification for political regimes that maintained the formal institutions of late-20th century democracy (formally competitive multiparty elections, elected presidents/parliaments, separation-of-powers structures for the judiciary, formal constitutional rights guarantees, etc), but was de facto authoritarian. Thus, the political playing field was systematically tilted and manipulated in a variety of ways to produce the same outcome sustaining a single ruler/ruling party.

While we dropped the initial entry of the term ‘illiberal’ from the continuing academic debates regarding regime proper, the word survived and was transformed over the course of the later 2000s to 2010s to reference something a bit different. Instead of referring to authoritarian regimes themselves, it was repurposed to describe the changing political experience of specific Central-East European states (Hungary and Poland, especially).

These countries had elected governments which began to push an aggressive, ‘conservative’ (the air quotes will make sense soon) policy agenda in explicit opposition to the assumed norms of the European Union’s elite leadership in Brussels, all in the larger regional context of a broader shift towards traditionalism elsewhere in Eurasia in places like Russia and Turkey. Yet for a variety of reasons, scholars did not connect this wave of new politics to previous forms of conservative or center-right politics in Europe, but rather termed it ‘illiberalism’ or described it as ‘illiberal,’ and framed it as (often also ‘populist’) political backlash and reaction.

By the late 2010s, there was a new, but already large academic literature on illiberal parties, policies, and governments in the region, and a concomitant effort to extend this discussion to states much farther afield in places like Southeast Asia or Latin America. This process of academic production was largely organic, and has relied primarily on a series of inductive case-studies in which x or y party/policy/government was asserted to be illiberal in one way or another, and its activities explained with this general framing. As one can imagine, starting in little Hungary and then extrapolating out to the global stage has led to some confusion and messiness.

Concepts vs. Descriptors

Indeed, there has been a tendency to mush widely disparate developments together in a way that could be (unkindly) described as ‘all bad things go together’ scholarship. So a litany of ‘bad’ states would typically frame discussions of illiberalism, linking Russia to Hungary to Brazil to China to the United States to wherever else in a sometimes handwaved fashion, which also included a series of other conceptual buzzwords like ‘democratic backsliding,’ ‘populism,’ and of course authoritarianism itself. While it’s entirely fair that a conceptualization of illiberalism could certainly apply in one way or another to a variety of cases - and may overlap with other such concepts (the answer turns out to be yes and yes), a core understanding of what exactly was meant had not really been established, so pretty loose usage was very common.

As a result, the term ‘illiberal’ has been often more a descriptor or a pejorative than a defined concept. In a truly colloquial sense, the word illiberal is just another way to say ‘not-liberal.’ And as things tagged as ‘liberal’ tend to be deemed normatively good by most scholarship in the West, it can easily be used as an adjective that simply implies ‘not-good.’ And that has been a problem, as the premises of social science research have ontological conceptual assumptions in both empirical and theoretical research. One cannot actually have a word that generically means ‘not-good’ and keep it as a rigorous concept able to be used effectively in applied research.

To explain in a sentence, a social science concept describes an identified social/political phenomenon in the real world (which ideally can be observed and measured and is asserted to truly exist) which is assumed (i.e., implicitly theorized) to have some kind of a patterned nature across a universe of cases. For example, a regime we label conceptually as ‘authoritarian’ will have some similarities to another regime we label as such, and the research questions follow from that - why, how, in what way, with what level of certainty, used as a dependent vs. independent variable for a causal or probabilistic question of interest, nested in which sub-concepts and sub-classifications, etc.

The concept will not explain everything about the country, and perhaps it might not explain most things. In fact it really shouldn’t be a mega-category that explains everything (this will fail or be useless for applied research purposes). But a well-contoured and delineated concept helps us identify and isolate some element of a political phenomenon as a true category that actually exists in the real world - and which we can study in-depth.

Grasping this helps us with why the concept problem can be really troublesome if a term is also being used in a generalized pejorative manner. The difference between a descriptor and a concept is one of comparative rigor: if we are using a conceptual definition of a term, it needs to travel across cases in a way that makes comparison meaningful, and scholars can assess similarities and differences in inputs, outputs, and processes as per above. If illiberalism is just ‘not good things,’ that doesn’t help us as researchers very much at all - we might as well not bother, or just throw out explicitly normative and even emotive words ‘bad’ or ‘evil’ and be done with it, if that’s our purpose.

Illiberalism has had exactly this problem - it was used very freely to describe very different political phenomena happening globally, with implicit theories baked into it rather than tested. And it overlapped with other concepts in a way that has often obscured more than helped. For example, very notably, illiberalism tends to describe something kind of like ‘conservatism.’ But it doesn’t actually, as scholars inductively seem to apply it only to a very distinct subset of global conservatisms, and the phenomena identified sometimes don’t even fit inside that term very easily. Hungarian conservatism, for example, was described as illiberal in the early 2010s, but conservatism in Germany, or France, or Spain rarely was. Similarly, Viktor Orbán is very rarely compared to Angela Merkel or Nicolas Sarkozy for reasons self-evident to regional specialists, but hard to explain if one doesn’t have a way to distinguish - so here, the concept of illiberalism helps, while that of conservatism doesn’t in this case.

As for closer to home, parts of American illiberal thought today are clearly ‘conservative’ (such as in regards to some social policy or traditional morality) but other elements are much closer to what Americans would describe in the vernacular as liberalism or progressivism (economic statism, military intervention-skepticism). So it has become clear that we’re dealing with something distinct that isn’t quite captured with other concepts. And it also doesn’t work to just say illiberalism is traditionalism, or something like that. Are the Amish illiberal? They are not-liberal, they are conservative, they are traditional - yes. But are they really in the same category as Orbán? Seems dubious.

The opposite works too - some of Hungary’s social policies (e.g., family policy) on their face are within the same general realm as those found in Sweden in the 1990s. And its moral assertions (about marriage, for example) are essentially normative in the West until the late-2000s. Was Sweden or the US or France ‘illiberal’ in 1998 or 2005? If so, we’re suddenly not explaining very much are we. Thus, we return again to the motivating issue - we have identified some sort of phenomenon in the real world, now we need to be rigorous and nuanced about what it actually is.

And illiberalism is still a capacious capacious, even if we can make the above distinctions. Good examples are the ur-cases of Hungary and Poland. Both have been described as illiberal (I think correctly), but they are distinct cases - despite notable similarities. Poland, for example, is an electoral democracy, while Hungary is a soft electoral authoritarian regime. Thus, illiberalism crosses the regime-type divide. Poland’s foreign policy is aggressively anti-Russian, while Hungary’s is much more equivocal and even sympathetic. Thus, illiberalism works across foreign policy orientations. Polish political culture is strongly associated with the symbolism and heritage of Western Christendom and Catholicism, while Hungary maintains a strong ideological sub-current tied to the unique ethnocultural imagination of Eurasia. Thus, illiberalism can work in distinct symbolic repertoires. And so on.

That only scratches the surface, of course. Research on illiberal politics in southeast Asia, for example, suggests that illiberal Islamic movements in Indonesia have been a bulwark for maintaining a competitive electoral regime and asserting certain civic rights (such as freedom of religion). Illiberalism in India, on the other hand, covers the newly-dominant, forthright Hindu nationalism and the undoing of post-independence India’s secular socialist legacy.

All share the same broad conceptual connection that defines illiberalism, which gets to our actual (clunky, but workable) definition of illiberalism. That is, an ideology of aggressive political reaction in the modern era against the assumptions and norms of ‘liberalism,’ in polities that have experienced political, economic, and/or social liberalization, insofar as it highlights “opposition to and reaction against philosophical liberalism, with pronounced tendencies towards the distrust of checking or minoritarian political institutions formed by apolitical experts, and focused on promoting a variety of collective, hierarchical, majoritarian, national-level, and/or culturally-integrative approaches to contemporary political society in a substantive manner.”

What this means in practice (and with less academic phrasing) is a constellation of political and policy orientations that often include a mix of cultural conservatism, religious traditionalism, a view of world politics based in civilizations, a rejection of the primacy of the individual in favor of the family, community, and/or nation, and the deemphasis of personal autonomy as the highest good relative to a view of a common or shared good as the goal of society. This means very different things in different countries at different times, and illiberalism studies continues to grapple with exactly how to connect - or distinguish - all of this in empirical research.

Where Are We Going From Here?

The reader can quickly find a great deal of frustration here - the terminology is still imprecise, the swathe of phenomena under study can be seen as achingly different by some or all connected by others, and there are tremendous overlaps with other important and useful concepts that needs continued disentangling. The reader would be correct in identifying these frustrations, as that is exactly the case. So what do we gain here, and where is this entire research agenda headed?

The second question is hard to answer, but the first is much clearer. By taking illiberalism seriously, we gain a way to talk, categorize, and research in-depth the massive, global reaction to the ‘way things have been’ since the end of the Cold War. No casual observer of politics worldwide would suggest all is calm in the domestic politics of a huge number of countries both near and far. Something like ‘populism’ or ‘authoritarianism’ gets us some of the way to describing changes in the global states’ system or the internal political orders of many states, but for others it falls flat or is imprecise in important ways. There is this amorphous, ideological component that most can see - and many can draw connections across - but it is confused, diffuse, and contextually-specific.

Illiberalism is a conceptual tool that can be deployed to help make sense of this. But it is a tool that is (possibly) fatally compromised by the pejorative nature with which the word is often deployed. That’s where this new generation of scholarship sits - trying to be rigorous, nuanced, and methodical about researching what amounts to a very dynamic political environment. And trying to do so in a way that allows us to dig deeper into these phenomena, while avoiding ‘all bad things go together’ assumptions. Whether we will be successful, of course, I cannot say.

For my own part, I’ve found that thinking about ideological change in Russia through the illiberalism lens has been productive and useful. Similarly, I find that comparisons between illiberal policy dynamism in Eastern Europe and ideological entrepreneurs in the English-speaking world has opened up a new way of thinking about our own political discontents much closer to home. It also provides a useful umbrella concept within which very different ideas and political actors can be placed, if only as a first-step to make some initial categorization sense. For these reasons, I’m quite certain that I (and many others) will be continuing this line of academic research for the foreseeable future.

Further Reading

This newsletter’s list of recent publications is unusually long, and runs the gamut from topics in illiberalism to those in the national-security/Russia studies world. Please don’t assume that my productivity is always this high, though. I’ve just been recently married, after all! For those interested, a small list:

First, I published an essay in the national-security online journal The Strategy Bridge on intelligence failures and bad political assessments pertaining to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. I use the disastrously incorrect picture of Ukrainian domestic politics and ideological change developed by Russia’s FSB as a reminder to policymakers in the US that careful, nuanced understandings of the domestic political environment in a country that is the target of kinetic interventions remains vital. You can find it here: “Intelligence Failures and Political Misjudgment in an Age of Ideological Change.”

Second, I published a working paper version of a book chapter on how to conceptualize authoritarianism that will be included in the upcoming Oxford Handbook of Illiberalism. The paper is open access at SSRN, and the chapter has been accepted - it’s still technically open for feedback and comments, and but will be finalized soon. You can find it here: “Illiberalism and Authoritarianism.”

Third, I published another working paper version of a book chapter, this one for an upcoming volume on ‘Social Catholicism for the 21st Century.’ The chapter is on the illiberal ideology of integralism, where I discuss it in relation to the broader illiberal/postliberal ecosystem of thought and how it fits into debates on democracy. You can find it here: “Integralism, Political Catholicism, and Democracy in the Modern West.”

Finally, I’ll note that I was invited on a podcast for a student org run by one of my former students. It’s available on Spotify, and we discuss illiberal ideologies and other related things. I haven’t actually listened to it, but if I remember correctly we hit a variety of illiberal phenomena in both Eastern Europe and here in the US. Find it here at “Prof. Waller on Illiberalism's Reactionary Diversity.”

- Julian

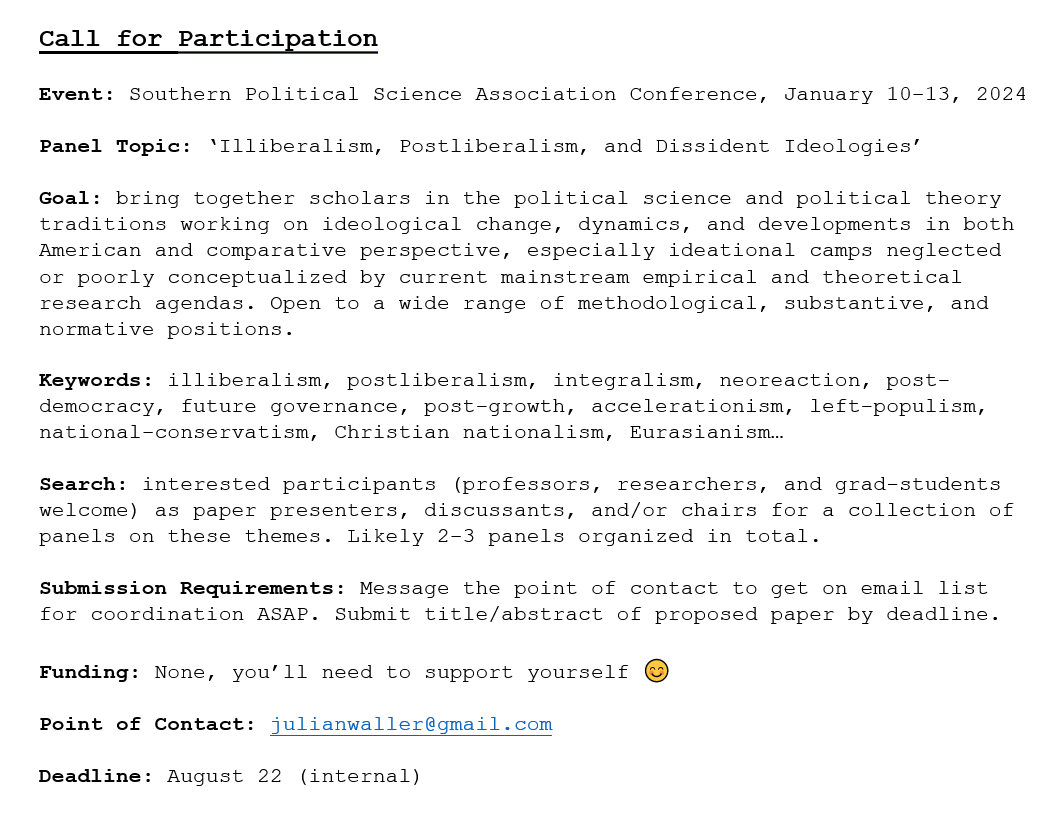

P.S. - I am organizing a set of panels on illiberalism and related (spicy) topics at the upcoming Southern Political Science Association conference (January 2024, New Orleans). If your academic research might fit the bill and are interested, shoot me an email and I’ll put you on the list for coordination. Paper idea/submission will be due later on this month. See the below graphic for more details: