Precis/TL;DR: in which we say a few words in honor of the departed Holy Father, and a few words more on insights into political order when looking at the institution his office governs. Publication announcements conclude the newsletter as always.

Some Introductory Words

We should begin this newsletter with a respectful and earnest prayer for the departed Holy Father Pope Francis. Requiescat in pace. May his soul take comfort in the bosom of the Lord as he finds his final resting place until the ending of the world.

As someone received into and confirmed in the Catholic Church under his shepherd papacy, I was sad to hear the news of his passing earlier this week. This newsletter is not one of evangelization, however, and I have no intention of moving to theological questions any time soon.

Instead, I would like provide a few partial insights closer to my area of professional expertise - and the interests of our readership, which naturally spans a variety of religious and areligious traditions. That is, an appreciation for the peculiar, and unusually effective, governance model of the Papacy.

Everything below is meant entirely neutrally and analytically. In fact, this is a good example of my own intentionally at-a-distance and highly conceptual approach to the study of political order and government here our temporal world.

Because today we’re going to briefly discuss the most successful authoritarian regime in world history.

The Papacy as Electoral Monarchy Perfected

Looking at two core elements of interest in the study of regimes - longevity and stable succession - the Papacy is impossible to best in comparative perspective. The institution itself is nearly two thousand years old, and has managed its perpetuation for just as long.

Even counting crises and considerable periods of strife (anti-popes, the Babylonian Captivity, faction and corruption, foreign influence, you name it) it has endured remarkably well. And in doing so it has maintained a unique form of internal governance with interesting theoretical insights for any student of political order.

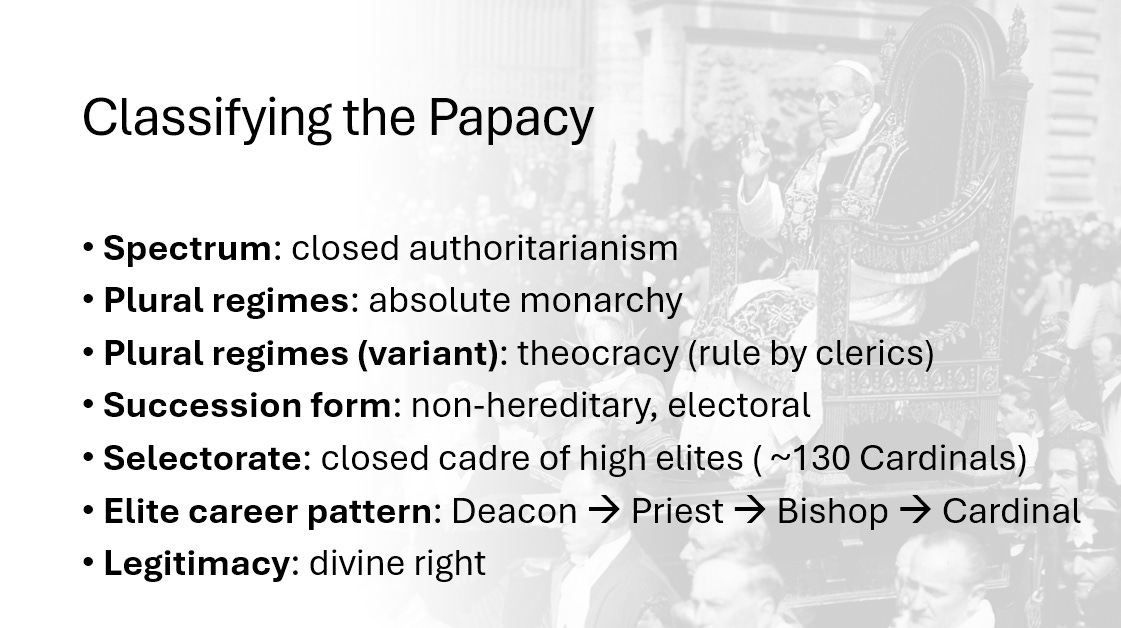

I brought this up to my students in the final class of our AUTHORITARIANISM 101 course (Spring 2025 - GWU) and asked a simple question: what kind of authoritarian regime is the Papacy, in the terms of academic art we have been using all semester?

They got the general contours of the regime correct. An absolute monarchy, in which succession is non-hereditary, but elective by a closed selectorate of high magnates (in this case Cardinals, a type of bishop at the top of the hierarchy of the Church). We can be more specific as well. Using several conceptual approaches, we can get the following abstraction of the Papacy’s governance model:

What is so interesting about the Papal model is that it maintains the decisive decision-making and authority profile of an absolute monarchy while including a surprisingly robust selection mechanism for succession. One that, very unusually, maintains considerable uncertainty over final outcome.

Normally, uncertainty over succession outcome is a hallmark of electoral democracy (that is one of the pillars of its conceptual definition, alongside multiparty competition and broad suffrage). The Papacy has neither of the latter two, but retains a highly institutionalized means of the first.

Indeed, Papal succession is a very complicated affair governed by canon law, intricate procedural layers, and allowances to both contain and manage (but hardly eliminate!) scheme and faction. Here is a great and easy-to-read article laying out all the moving pieces. For another on the constitution of Vatican City itself, see here.

The ability to allow for genuine uncertainty over succession is due to the unique degree of elite buy-in to the regime with extremely long time-horizons. The elite selectorate of Cardinals is grown up in the regime from the beginning, starting as Deacons, becoming Priests, and then Bishops. There is a clear career trajectory. They are aligned on the mission of the regime - saving souls and guarding the faithful unto the Second Coming - and know that they are a small part of a vast, legitimating plan.

This is tremendously useful, as it means genuine choice among the high elites can be expressed (in the controlled environment of a rarely held Conclave) without fear of regime collapse. In fact, there is an analogy to the ideal of the party regime, but in a pre-modern, feudal format.

Put simply, every Cardinal is a member of the single party, they are invested in it, and they are united by close institutional and ideological bonds. There are internal mechanisms to solve disputes and adjudicate leadership. Elite splits are discouraged from metastasizing into disruptive exit but rather channeled through institutions. And the decentralized nature of the rest of global Church governance, spread across thousands of dioceses, religious orders, and societies, means ambition can be satisfied in many corners of the wider governance structure.

Of course, if you are Catholic, you know that the Holy Spirit further plays a role in leader choice. And if you are not, you can still admire the institutional structures that help solve the perennial problem of orderly succession.

To sum up, the Papacy is a highly effective and highly unusual form of electoral monarchy. Perhaps its finest expression. Of course, none of this means that there may not be crises or failures or disappointments or even interventions from the outside. Succession can always ‘go off the rails’ even in regimes with proven track-records. We live in the empirical world, and that world is quite fallen.

But from a comparative perspective, and in the long run of human history, no other actually-existing and recognizably coherent regime has ever lasted so long. Not the dynasties of Imperial China, not the Roman Empire, not the ancient realms of the Egyptians or Babylonians or Aztecs or Incas, and certainly no modern state. The Papacy may very well be a sui generis model of political order, but it is still a highly instructive one.

Institutional Innovations in Catholicism

It is worth noting that this is not the only surprisingly effective expression of institutional innovation that has come out of the Catholic Church’s two thousand year history. A few points are worth mentioning here, simply because they are interesting.

First, some of the core ideas of representative government come out of Catholic religious orders in the high middle ages. This has been noted by a set of Scandinavian political scientists recently, focusing on the particular form of internal governance practiced by the Dominican Order, among other innovations of the medieval era. You can read a non-academic version of the general account by Prof. Jørgen Møller here.

Just to take the the Dominican example, we can see how governance technologies developed within church institutions ended up informing later evolutions in the secular world. The Dominican case involved religious chapters electing representatives to congregate in a single location to decide internal leadership questions.

In doing so, they developed the concept of plena potestas, that is, the idea that a representative was given the political power to represent his constituency and that decisions then made in plenary with other representatives collectively would then be binding on all (sometimes “plena in re potesta” - “in full power [to do what one wills with that which one commands]”).

That is, the representative would not need to return to his constituent in order for them to approve the decision. This is the core idea that makes representative democracy outside of the bounds of a single city or small territorial parcel work and transforms those sitting in assemblies from de facto diplomats or emissaries to de jure representatives and parliamentarians.

Second, the medieval experience of conciliarism, a model by which doctrinal decisions would be made in a collective setting through regular, institutionalized meetings. This too developed during the medieval period. Although it would fall out of favor relative to centralizing decision-making in the Papacy’s absolute monarchy, it would deeply inform the development of parliaments, diets, and assemblies in late medieval and early modern Europe.

Seeing the Church work in this way would be an impetus for feudal and nationalizing polities in Europe to do the same. It combined with old traditions of acclamatory and advisory councils for monarchs to create far more permanent assemblies.

The picture here is quite complex, naturally, with many causal processes interacting together (including the necessities of constant, internecine European wars and the growing expense of military force). But the Church played a role in modeling a major shift that would ultimately culminate in recognizable democratic (or rather, representative) institutions.

Finally, the Church is genealogically responsible - in tandem with its inheritance of the legal customs of the Roman Empire - for the law codes of all Europe (outside of the British Common Law tradition). The Roman law would form the basis of increasingly complex legal architecture across Europe, which would in turn be standardized further under Napoleon centuries later.

The people over at the Ius et Iustitium Substack are all about this legacy (along with more modern legal discussions), but it forms a key element of the famous Marxist social theorist Perry Anderson’s explanation of evolving European governance in the Early Modern period as well.

Final Thoughts

I had not been intending on covering the Papacy in my course this semester, despite the topic being explicitly on European and Eurasian experiences of authoritarianism. One should not extrapolate out too much from outlier cases, especially ones that hold nearly no physical territory by the modern era.

But nevertheless it was refreshing to take a glimpse at a governance model as peculiar as this one. And a great benefit of taking my course is exactly this kind of thought exercise (for what it’s worth, there is already a wait-list for next semester, but you still have a chance!).

Even so, I don’t really recommend ‘building the Papacy’ as a viable model for autocratization or stabilizing authoritarian rule today or in the near future - one wouldn’t know where to begin, frankly.

But it’s exactly the sort of odd case that makes for a fun newsletter to ponder over.

Further Reading

There are no new reading updates since our last newsletter, but I will highlight the two most recent additions to the CV:

First, I have a new book review out on Jerome Copulsky’s American Heretics: Religious Adversaries to Liberal Order (Yale University Press) published at FUSION. I argue that Copulsky’s work, which is a refreshingly neutral look at religious-inspired critics of America’s political and social order across the centuries, is also a tale of American nationhood and its challenges. You can find “National Heresies” here.

Second, I have an article out at West Point’s Modern War Institute on the collapse of the Syrian regime and what says, and more importantly doesn’t tell us, about authoritarian regime durability and threats to survival. Read “Bashar al-Assad and the Oversimplified Myth of Autocracies' Inherent Fragility” here.

Finally, do check our the previous newsletter - our first installment in an occasional series on the Authoritarianism of Tomorrow:

An Outside Reading Corner

Although this newsletter is not about evangelism, it would be remiss on this very specific occasion if I did not gesture towards some reading for the religiously curious. I’ll give you two for now, and you are welcome to reach out for more.

First, if you are genuinely seeking insight into Catholicism proper, I strongly suggest a summary book called The Light of Christ: An Introduction to Catholicism by Fr. Thomas Joseph White. He is now the rector of the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas in Rome (known as the “Angelicum”) and also plays bluegrass with a bunch of Dominicans. It is an excellent introduction to Catholic theology and touches on all the various hot-button issues the modern reader will be concerned with.

As you can see from this screenshot, I purchased it in 2020 and crossed the Tiber two years later.

Second, for an ecumenical and historical approach to Christianity and its legacy in Western culture, I highly recommend the British historian Tom Holland’s Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. Holland is a fabulous writer and was an agnostic at the time, so it is very accessible. I can play the same game as above, and this one is particularly helpful to get a full-spectrum temporal angle.

That’s all from me for now!

- Julian