Précis, aka TL;DR: in which we discuss differing ways to characterize Russia’s current political regime and what that means for analysis by social scientists and policy researchers in the West. Wartime Russia today is ultimately best understood as a personalist dictatorship (with an increasingly coherent and deepening illiberal ideology), although retaining the institutional architecture of prior years formally intact, thus far. This makes it likely to be resilient in the short- to medium-term, but uncertain once the question of political succession becomes active. A concluding section notes a few recent publications announcements.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War in February 2022, a variety of analysts and commentators have revisited the old question of what modern Russia ‘is’ in a political sense. The question is a good one, as wartime conditions often warrant a qualitative shift in the nature of a given political regime. Sometimes only so long as the state of exception lasts, other times marking a longer-term shift in its domestic politics. This question can be similarly applied to Ukraine - for example, whether elections will ever be held while Ukrainian territory is under occupation by Russian forces, is a very live concern. We will table the Ukrainian case for now, though, and focus on the Russian.

So, why do we really care about what the Russian regime has ‘become’? For one thing, understanding contemporary Russia’s political system can help us better assess how decisions are made, which political actors matter in the system (and how they influence it), and identifies the parts of the system that we can watch while we wonder about outcomes of interest. In more concrete terms, knowing how to typify Russia’s regime can help us figure out how succession may function, what the dangers are to the regime’s stability in the coming months and years, and where challenges to the status quo may come from. Among many other questions.

There are also more evocative questions that are popular as well, which lends weight to discussing this thoughtfully. Is Russia a ‘fascist’ state? What does that even mean? Is it ‘totalitarian’? Is another label better suited? Does today’s Russia represent an experiment that may be replicated or modeled elsewhere? Previous decades of similar assessments have helped us, not least noting (for example) that Russia’s political model has been previously viewed with interest by other states in the wider region and in many ways pioneered a very effective method of 21st century authoritarian rule. But that’s the recent past, and we know things are different now - so how different exactly are things today?

We can get at this problem by working with two large frameworks, suggesting a few different typological approaches, and a few ideological labels as well that might enlighten us. Unsurprisingly, wartime Russia is a moving target, and so this is more a thought-exercise set by developments current to autumn 2023 then a final conclusion.

What Russia Was

We are pretty sure we understood what Russia has been in political regime terms for the last decade, as well as the decade prior - which was, contrary to some assumptions, actually a bit different. It gets a little more difficult if we go back to the 1990s, as there is a refreshed debate on how we should think about Yeltsin-era Russia. Let’s take these quickly in turn (working backwards) before we get to Russia today.

Pre-war Russia from around 2012 to 2022 is fairly easy to categorize using some standard regime concepts. It was an authoritarian regime for sure, that’s no problem. It had an executive that was dominated by a personalist and personalized approach to political authority and decision-making centered on President Vladimir Putin and centralized in the executive’s Presidential Administration, which developed the vast majority of policy and political decisions. And it still held to the formal, de jure trappings of the liberal-democratic constitution that had been written in 1993, most importantly maintaining elections at the federal and regional levels, while sustaining a multiparty parliament and a standard higher court system.

Thus, the Russia of the immediate past was what we would call an hegemonic electoral authoritarian regime (according to a typology that focuses on institutions) and a personalist authoritarian regime (using a typology looking at the nature of power at the apex of the system). Comparable states could be Kazakhstan or Belarus in the post-Soviet space, Venezuela in Latin America, or Uganda in sub-Saharan Africa - although all these comparisons are not exact and requires the usual nuance and exceptions. It also had a vague, but noticeable state ideology that we can call illiberalism, which was a complex of geopolitical anti-Westernism, cultural conservatism, and social traditionalism.

By the way, here’s a graphic that I usually show my students as a typological cheat-sheet for some standard nomenclature for the ‘spectrum’ approach to political regime taken from the ‘New Authoritarian Institutionalism’ school of comparative political science, which basically categorizes based on how closed or open (i.e., pluralist) the system is, using elections as the primary fundamental marker of political difference):

Before 2012, Russia under Putin was a bit different, although certainly in a similar ballpark. The same formal, political institutions existed as they would a decade later, for example. The key distinctions here would be a relatively more pluralist political system (especially 1999-2004), and relatively less personalism in the executive. Critically, this period had the Medvedev presidency as an interlude, which halted and confused some of the single-figure personal authority that would typify the regime after Putin’s return in 2012. For some time, scholars genuinely even were a little confused about the mixing of democratic institutions with an increasingly unfair political playing field, one that interacted frustratingly with high regime popularity and the desultory state of the formal political opposition.

Russia in the 2000s thus tracked generically as an electoral authoritarian regime as well. But more open and with less repression than after 2012. The regime-with-adjective concept of ‘competitive authoritarianism’ was coined at the end of the decade for this sort of less coercive, more pluralist variant. Some would call this a ‘hybrid regime’ as well, which highlighted the less ‘clearly authoritarian’ features of the polity. The place of the ruling party, United Russia, was also sometimes seen as a distinguishing feature, and Russia might be called dominant-party authoritarian regime (rather than a personalist one). The party was weak and subordinate, but still a distinguishing feature of the regime and effectively coopted and coordinated essentially all relevant political elites in the country. In comparative terms, we can fruitfully point to Turkey, Hungary, Venezuela (again), Singapore, and Malaysia as other useful cases, and with some stretching maybe Zimbabwe or Tanzania. Ideologically, the regime at the time was not clearly anything specific, mixing neoliberal economics, state-patriotism, social moderation, and geopolitical sovereignty emphases. The regime’s political curator at the time, Vladislav Surkov, called this ‘sovereign democracy,’ but it was fairly broad and in many ways was defined primarily by the apolitical nature of the regime’s preferred, de facto social compact.

Finally, Russia in the pre-Putin 1990s is a bit difficult. Traditionally, it’s been understood as an electoral democracy (note again, the same institutions formally existed in 1994 as they did in 2022) both in the West and in Russia itself. In fact, much of the relative distaste that the word democracy has in Russia comes from calling the 1990s a time of democracy, full-stop. As the 1990s are not remembered well, generic ‘democracy’ has a sullied association for some in Russia. There are, however, arguments that Yeltsin’s Russia did not hold sufficiently fair elections to really qualify, or that it ‘never democratized in the first place.’ And that debate is actually being invigorated now, so deserves a separate discussion for another time. But it is a useful point of departure to note a different typological approach that might eschew the standard democracy-authoritarianism framework and rather call 1990s Russia an elective oligarchy. This would be to emphasize the pluralism and tense political chaos of the period, highlighting the multiple factions of wealthy and powerful individuals fighting over politics, without the higher bar of free and fair elections (etc) that we usually reserve for democracy. I’m not sure how far I’d want to go on this one - a topic for a separate essay, perhaps - but it’s a point of interest nevertheless.

So that’s what Russia was, or has been, since the fall of the Soviet Union. But what is it today?

Typological Approaches

In one sense, contemporary wartime Russia seems radically different from the previous era. There is an obvious state of exception in place, with a variety of ad hoc contingencies and institutional shifts that seem to make its public politics very distinct. From that perspective, Russia is a personalist dictatorship, period. But in another sense, there is notable continuity. Elections have not been cancelled, the parliament still meets, the parties are still there, and so on. The administration, for what it’s worth, clearly still thinks multiparty elections are important elements to the formal political system. Just because the regime is more coercive doesn’t mean that it still can’t fit the older schematic model of hegemonic electoral authoritarianism or something similar. And we could also take cues from the classical world and think a bit more premodern, naming Russia an autocracy (which is quite similar to the first), but mean something closer to monarchy - or even tyranny. We can therefore think of this in three distinct typologies that help us make some categorical sense of things.

Taking the first frame, of Russia as the personalist dictatorship of Vladimir Putin, gives us exactly that. A pure personalist authoritarian regime, in which politics is directed - often manually - by the apex political leader who commands through personal loyalties and an overwhelming concentration of political authority, with no other centers of real power in the country. We can see this, for example, in the growing rhetorical tic of a variety of Russian politicians to refer to President Putin as the ‘Supreme Commander-in-Chief’ (Verkhovniy Glavnokomanduyushchiy), which underlines the quasi-military nature of his political legitimacy. Some time ago, the Russian political scientist called this Putin’s “warlord legitimacy.” Using ‘dictatorship’ here we can also note the de facto state of exception operating given current wartime conditions. We can also see this through deinstitutionalization processes, by which ever more policy-making is centered in the executive (and taken from the ministries or other policy-influencing entities), while ad hoc committees and personalized subordinates proliferate as the primary means of making decisions and shaping policy. The further prominence of Russia’s Security Council as a pseudo-‘royal court’ of sorts also suggests this sort of personalized system.

Taking the second frame, of relative continuity, actually gets us the same answer as 2010s Russia - an hegemonic electoral authoritarian regime. No institution has really changed, and all the gearworks of the old constitution still exist. Just holding elections or having a legislature doesn’t make you an electoral authoritarian regime, but having the electoral and party processes make up an important element to the overall political order, inform the nature of elite hierarchy and institutionalized lines of authority, and ensure the formal inclusion of non-government elites (with potential institutional privileges) in the broader system does. Russia just had regional elections, which actually included a few non-United Russia wins, the Duma is still operating as it had been in the late 2010s, and the Kremlin has sharply rebuffed proposals to create any sort of uniparty or single-party front. Elections for the president will be held next year (although those may be uncontested, which of course would be a formal mark against). And it generally relevant to keep these sorts of formal political institutions in mind, as holding elections during wartime can go off the rails due to their nature as focal points for expressing political discontent - in theory, at least.

A third view would be to recourse to older classical categories and simply call Russia an autocracy - that is, a de facto monarchy (albeit with no successor)… or its darker twin term, tyranny. The traditional Aristotelian-Polybian categories are usually underspecified, which is why we tend to like sub-categories with more information in them (like ‘electoral authoritarianism’ and so on). But in the current Russian case, it might be valid in a generic sense. Usually ‘autocracy’ is just a synonym for ‘authoritarianism’ for scholars today, but it shouldn’t be. The latter is a broad umbrella, the former really does emphasize singular rule in one person (with the monarchy-tyranny distinction depending on if the ruler is using power for the common good or personal ends). So using ‘autocracy’ for Russia today, unusually, does accurately convey the case context. It also gives us a bit of a premodern flavor that might provide some analogic sense to things like the summer’s Prigozhin Rebellion, which in many ways can be best understood as a kind revolt by a ‘political-military baron’ against the monarch - not to overthrow, but to negotiate with the apex power-holder in the polity from a place of armed strength. Prigozhin lost that fight and Putin won, but that doesn’t deny the potential analytic utility.

For the purposes of understanding how decision-making is working in wartime Russia today, it’s likely that the personalist dictatorship framing makes the most sense. Especially if we include the close coterie of upper-tier elite actors and the institutions they sit in (the unelected Security and State Councils, respectively). These hierarchically-subordinate bodies are not ‘checks-and-balances’ on the executive in the way that the parliament or courts nominally could be. Rather, they are assemblies of key notables and decision-influencing actors who have a subservient relation as core, loyalist vassals to the president himself. Autocracy alone is something to keep in mind too, if a little less specific but fitting with some of the neo-medieval analogizing. But we can’t sleep on the fact that the formal apparatus of governance is all still there. This doesn’t necessarily matter for policy-making (although, as a topic for another time, the Duma is absolutely still engaged in substantive law-development and the parties are desperately trying to maintain relevance), but it will matter a great deal more in a succession or regime transition, should we see one.

Ideological Approaches

There are other ways to understand the Russian wartime regime, of course. Many focus on ideology, or ideology-adjacent concepts. Here is where we get the perennial ‘Is Russia Fascist’ debate, among other things. We’ve certainly seen an uptick in ideological crystallization and conformity, which I’ve written about recently elsewhere. For the time being, there’s one good way to bring ideology into the regime conversation, and one bad one.

The right way to think about ideology in Russia at present is through the concept of illiberalism. This denotes a broad, ideological reaction against the assumptions and perceived power of Western-style liberalism (political, economic, and cultural) and in the Russian case is defined by an officially-sponsored turn towards anti-Westernism, cultural conservatism, social traditionalism, and civilizationist legitimation. Illiberalism has been present in Russia at the regime-level since the early 2010s, although it has been in a process of gradual development.

Since the war, these processes have ratcheted up significantly, and we can be quite clear that illiberalism is very clearly the official ideology of the regime. The Russian state educational complex is busy drafting and preparing whole courses for university and secondary schools on Russia’s unique civilizational role in global affairs and the foundations of Russian identity and historical memory (look up the so-called ‘pentabasis’ concept for more there), and Putin speaks regularly of Russia as a ‘civilization-state’ aligned with the rest of the non-Western world. Russia obviously has an ideology in the way that it did not until ~2012, and it is far more open and defined than it had been pre-war. It is also far deeper than before 2022, with illiberal rhetoric pervading the vast majority of elite discourse and undergirding discursive frames in media, politics, education, and other spheres much more visibly.

The wrong way to think about ideology in Russia is to code in one of the early 20th century ‘isms’ as the key to Russia today. Usually, that means thick, but contested, labels like ‘fascism’ or ‘nationalism,’ in practice. Russia is not fascist, full stop. It doesn’t fit any relevant definition of that historical phenomenon, and as always using the label obscures more than reveals. At best one can perhaps suggest degrees of similarity between historical fascism and Russia’s conduct in Ukraine specifically (this is heavily debated at this very moment) but not for the domestic regime. And there is little evidence for the totalitarian approach to total society mobilization that typifies fascism (and communism for that matter). For those sympathetic to the f-word argument, you’ll have to wait for a longer form treatment of that, but suffice to say the evidence isn’t there and is far too motivated to be analytically useful.

In the meantime, while the case can absolutely be made that Russia today is in some way ‘nationalist,’ it is a very specific form that doesn’t make for easy comparisons and allows for a notably multiethnic, multiconfessional, and imperial version of the idea. There are, of course, plenty of ethnonationalists in Russia - although interestingly they are often regime-critical. The complex form of nationalism (or perhaps better, ‘national-patriotism’ or ‘imperial-nationalism’ or ‘civilizational-nationalism’) that does exist in Russia can already be captured in the illiberalism construct, and harkening back to old forms of ethnonationalism is, for now, less relevant. Again, as above, there is something to the war in Ukraine that has a greater nationalist flavor than the domestic regime, which complicates the picture. But if we are characterizing the internal regime itself, nationalism doesn’t get us that far yet, compared to the more diffuse and wider-scoped illiberal emphasis on civilization and culture. Perhaps for the next regime Russian nationalism might be more central, of course.

Concluding Thoughts

This discussion leaves us with a tentative answer to the question of ‘what Russia is today.’ It is a personalist dictatorship in a state of exception, under the sole, autocratic rule of Vladimir Putin, with the formal trappings and internal political institutions of an electoral authoritarian regime, with an official ideology of illiberalism defined by a coherent matrix of anti-Westernism, cultural conservatism, social traditionalism, and (state-)civilizationism. Or more curtly, an illiberal dictatorship, if you’d like. For the time being, it’s no longer really appropriate to compare Russia to its peer electoral authoritarian regimes, which leaves us in a little bit of an analytic dead zone. There is a uniqueness to contemporary wartime Russia that follows from the combination of Putin’s personality and personal management of politics, the system of power relations that has developed around it, and the formal institutional architecture that still very much remains.

What follows then? Well, personalist dictatorships (in general) have a tendency to survive fairly well - until the end of the leader’s natural life. At which point they have a tendency to fail at managing succession, ushering in considerable political uncertainty with the death of the executive. This sort of statement is probabilistic, rather than determinative, but as I’ve suggested before, succession remains the vital looming problem for Russia. The personalized nature of decision-making has, and continues to, deinstitutionalize the regime, with the exception of certain, court-like subordinate council bodies to the president himself, which are likely to hold the keys to the future. The United Russia party is weaker than ever (and it was always more a vehicle for collecting elites than a cohesive political entity), while regional governors have been systematically chosen for loyalty and ensuring local quiescence, rather than effectiveness, ambition, or creativity.

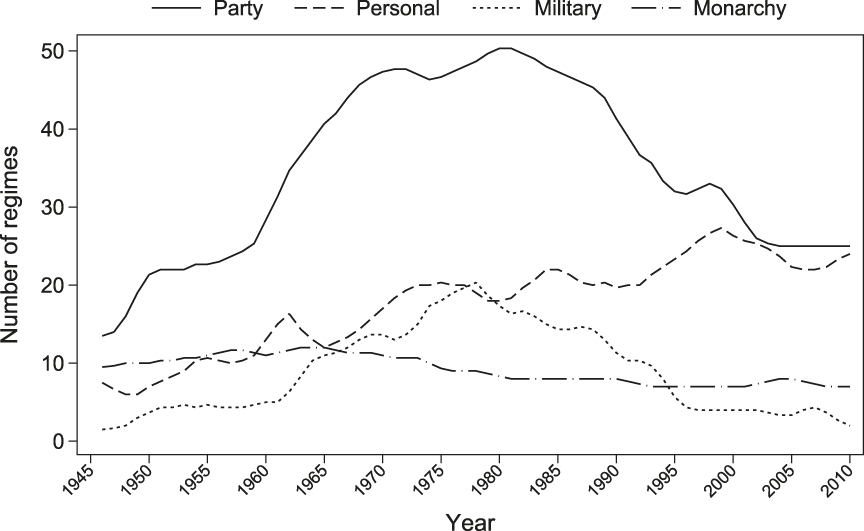

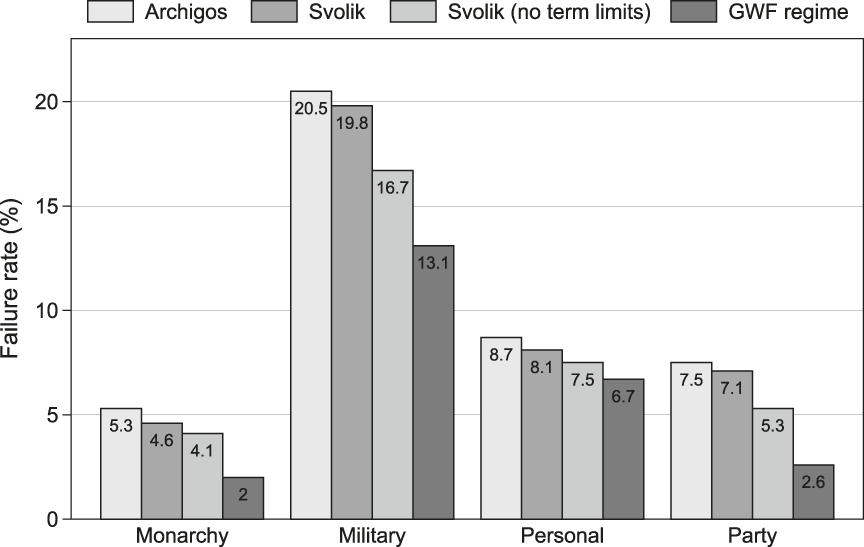

As a note, here are two charts using the ‘Plural Regimes’ school of comparative authoritarianism scholarship, pointing out total number and rate of failure for structurally differing authoritarian regimes. We should note here that if Russia is indeed a personalist dictatorship, that bodes relatively ill for future stability, although not as bad as a junta or military regime.

There are ways to reinstitutionalize the Russian regime, and turn it away from the personalist setup it has transformed into. But this is always hard to do (strong parties are really hard to build!), and there are many incentives to retain the basic structure for those who have benefited from the system. Should Putin pass unexpectedly or become incapable, one scenario worth thinking more about could be a tutelary situation, in which the current cohort of upper-tier security-service elites (FSB, Rosgvardiya, other siloviki, etc) end up running the country in a de facto regency or interregnum period. This might ultimately transform Russia into a somewhat unusual military (security) regime of some sort. This wouldn’t fit what we usually mean by ‘institutionalization,’ but might work as a transition point to a new personalist regime down the road.

Finally, the gradual and then quite sharp ideological developments in Russia are unlikely to be undone quickly, if at all (for the usual ‘foreseeable future’ period). Russian illiberalism is sufficiently internally coherent, has a variety of institutional supports both in state and in society, has a natural opponent in the ideological changes that have taken place in the West to compare itself to, and is sympathetic to other ideological currents rising across the non-Western world. It is very plausible that it will, indeed, be an element of continuity in the future, post-Putin world.

Where Russia goes in the months and years to come is anyone’s guess, and political scientists are famously bad at predicting major political events in Russia. This exercise gives us a small vantage point into how to think about Russia now, which may - or may not - help us in the future.

Further Reading

A few new pieces have come out since the last newsletter, although I am mostly still waiting on some larger articles to get through peer-review.

First, a short article in Russian Analytical Digest on illiberal discourse and political framings in the public Russian policy community. I suggest that civilizationist and anti-Western forms of illiberal rhetoric are increasingly de rigueur in Russian policy discussions and dominate the ways in which Russian lower-tier elites and adjacent policy communities talk about the world. You can find it here: “Elite Political Culture and Illiberalism in Wartime Russia.”

Second, a review of Patrick Deneen’s new book Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future, which I was asked to write for the small Catholic culture-and-politics publication The Lamp. I try to be sympathetic to Deneen’s intellectual goals, but find the book to be fairly disappointing as a new entry in the ‘postliberal’ thought ecosystem emerging in the English-speaking world. You can find it here: “Regime Actors: A Review of Patrick Deneen’s Regime Change.”

Third, our upcoming scholarly book published at University of Michigan Press now has a website, a few reviews, and a release date (August 2024). You can find that here: Autocrats Can’t Always Get What They Want: State Institutions and Autonomy Under Authoritarianism.

- Julian

I was wondering if I would see "hybrid regime" and I was not disappointed. Kudos. Jokes aside, I would argue that the current Russian regime is just another iteration of the same (maybe even unique) regime that has been in place since the end of the Mongol Yoke, with its main characteristics, per historian Andrei Fursov (yes, I know), being 1)supralegality and 2) existence of a single political subject that would actively oppose emergence of other independent political subjects.