Classificatory and typological thinking is central to the very origins of the comparative authoritarianism research field in political science and its predecessor disciplines. One has good grounds to claim that such thinking is indeed central to the study of politics and government in general. Scholars love categories, of course, but at least for political scientists they do so for one major, overarching reason: a good category type can suggest an underlying ontology. That is, if we believe there are real, true patterns to the social and political world, either true for all times or even scoped down to just a given region or time-period, identifying a ‘type’ that matches this reality can tell us what patterns to look for and how we might expect them to explain what we observe in day-to-day and year-to-year politics.

This is why it is analytically useful to spend time describing the contours of political rule in a given state (here: ‘political regime’) in certain ways, in order to separate out types that we think have relevant meaning in the social or political world. Typology is very old in the study of political regimes - one very simple division is something like ‘monarchy’ versus ‘republic,’ for example - but as we shall see there are many ways to slice such things.

This is not a question, or a way of thinking, reserved for academic discussions. Although it certainly can get into academic weeds. Yet we can readily observe how these ideas easily merge into debates that may involve something like widespread ‘received wisdoms’ that many of us share. It’s very common these days to say something like ‘autocrats think fundamentally in terms of their own security,’ or ‘democracies are better for human flourishing’ (or for economic growth or personal freedom, etc), for example.

These statements take as given an ontological assumption and assert a sort of generalized causality, telling us that a specific type of thing (polities led by an ‘autocrat;’ regimes we call ‘democracies’) will act in a certain way, or lead to a certain, ideally measurable, outcome that we care about. When we say things like ‘Russia today is a personalist autocracy’ but Singapore is a ‘dominant-party electoral authoritarian regime,’ these distinctions hold weight because the descriptors provide substantive information on how their politics works and how decisions are taken. That’s the goal, in any case.

Indeed, the draw of typology holds a very old pedigree when we want to talk about government. The Classical Era philosophers developed both the famous tripartite division of the ‘just’ regime (monarchy-aristocracy-polity) and its negative mirror-images (tyranny-oligarchy-democracy) as well as detailed constitutional analysis, such as the 158 city-state constitutions sketched by Aristotle and his students. Medieval and early modern scholars built out a related literature in the form of ‘mirrors for princes,’ which were written as advice manuals for rulers informed by explicit theories of rule. This genre included sophisticated works by Saint Thomas Aquinas, Niccolò Machiavelli, Jean Bodin, and many others. These writers ran with inherited older Aristotelian and Polybian accounts of political regime, and attempted to assess what exactly was best: usually variations of ‘mixed’ schemas for ordering power that favored either an aristocratic-republican or monarchic core.

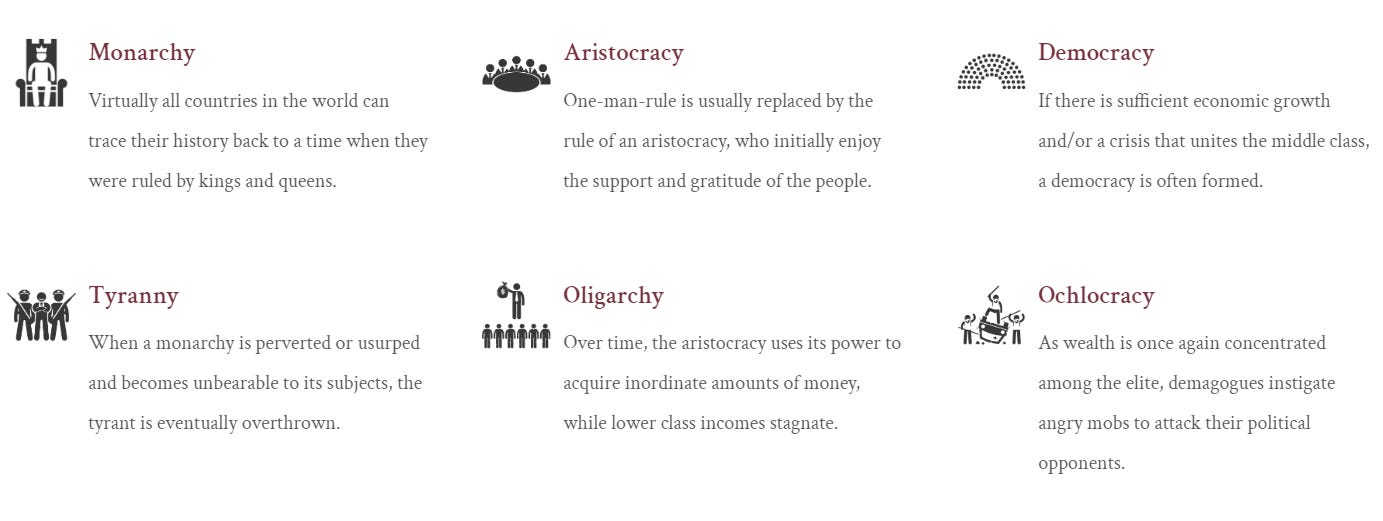

To illustrate, here is an example schema of the Classical tripartite conceptual division, taken from the curious Anacyclosis Institute. You will note that Classical typologies include not only normative aspects (‘just’ versus ‘unjust’) but also theoretical assumptions about how regimes degrade from one type to another, built directly into the typology:

Enlightenment thinkers, such as the Baron Montesquieu, and their applied readers, like the American Founders, were similarly oriented towards specifying institutional divisions and organizational boundaries as key to structuring the ideal polity. This was not limited to the ‘liberals’ of that age, but included as well counter-enlightenment thinkers defending monarchy and untrammeled executive power, from 19th century Spanish and French reactionaries like Juan Donoso Cortés and Joseph de Maistre to the exemplar authoritarian theorist of the first half of the 20th century, Carl Schmitt. The close study of political regime has not historically meant that one must needs support government by Madisonian checks-and-balances, let alone electoral democracy properly speaking - an interesting difference from a good deal of today’s working assumptions.

Much closer to our current age, the dawning of political science as an American academic discipline distinct from both the legal field and from Germanic sociology was strongly undergirded by an interest in explaining regime by categorical type. These modern political science efforts are somewhat divorced from the Classical, medieval, and early modern traditions, although not entirely. This disciplinary separation also sifted our understanding of regime out and away from the 19th and early 20th century world of comparative constitutional law, which had been the principal inheritor of premodern and early modern thought on the matter. Recourse to explaining political reality by regime type (a more sociological way of thinking) rather than by written constitution has had longstanding effects, including privileging (for perfectly good reasons) more abstract, conceptual frames and downplaying both ‘paper’ outlines of how politics are supposed to work in any given country as well as incentives to treat every political system as sui generis and difficult to compare cross-nationally.

If we wish to trace the most direct origin of the modern typologies in use today, the comparative authoritarianism field today is mostly derived from the modern categories developed concurrently by Carl Friedrich and Zbigniew Brzezinski and by Hannah Arendt in the 1940s-50s. These parallel projects separated out ‘totalitarian’ systems from more prosaic ‘authoritarian’ alternatives to explain the particular forms that harsh, ideocratic movement-regimes in Germany and the Soviet Union took in the 1930s. The modern, university-based study of regimes in this manner is technically some decades older, but the terminology and frameworks really come from the immediate post-WWII years, concomitant with breaking out political science as a discipline unto itself.

Given the paucity of true totalitarianism after the deaths of Stalin and Mao (with exceptions made for North Korea and a few borderline cases), the vast majority of comparative authoritarianism scholarship has concentrated rather on non-democracy’s far more empirically regular varieties of political order. The project to dive into authoritarianism proper was carried out most notably by Samuel P. Huntington and Juan Linz (alongside many others) by the 1970s, although we sometimes forget how that happened and what the debates actually were at the time.

This legacy gives us our generic term - ‘authoritarianism’ - which (implicitly or explicitly) means anything that isn’t the political regime we call ‘electoral democracy.’ Yet just briefly scanning the centuries gives us a vast swathe of terms, labels, and understandings of what political order looks like that technically all fit within this cavernous label. How do we try to make sense of all this in 2022, inching ever closer to a century on from the start of the modern study of regimes?

Analytical Schools of Comparative Authoritarianism

The current academic literature in many ways can be stylized as sitting primarily in two (mutually overlapping and sometimes complementary) analytical camps. We can call these the ‘New Authoritarian Institutionalism’ school and the ‘Plural Regimes’ school, respectively. The former is an analytic frame, the latter an explicitly typological one.

The New Authoritarian Institutionalism is built around insights and methods from political economy, primarily focused on assessing and explaining the utility of institutions in enforcing and undergirding stable political equilibria in authoritarian regimes. This school of thought, which is particularly rich and influential for its rational-choice clarity, posits that there are fundamental assumptions about non-democracy which unite the diversity of authoritarian regimes into an eternal series of difficult coordination, cooptation, and commitment dilemmas between a given apex authoritarian ruler and his or her subordinate elites.

In this reading, the politics of authoritarian regimes (i.e. any political regime that is not an electoral democracy – often shorthanded generically as ‘dictatorship’ or ‘autocracy’) can be understood with reference to strategic logics of regime maintenance: rulers choose to go it alone, institute organizational patterns, establish constitutions, and/or manipulate institutions such as political parties (none, one, or many), parliaments (yes or no), judiciaries (embedded, empowered, defanged), security services (coup-proofed and splintered or unified and coherent), and other entities to solve the problem of survival over time by providing rents and credible commitments – or not – to a given elite core.

This core group is sometimes termed the ‘selectorate’ - the collection of elites who do not rule, but to whom rulers must substantively listen to in order to maintain their authority. This approach relies on implicit or explicit assertions of ruler intentionality – an institution like a parliament or a ruling party is put in place to solve an information asymmetry or a coordination dilemma. This sort of logic thus takes an instrumentalist cast not dissimilar to the older analytic approach of ‘structural-functionalism,’ where an institution that we observe exists to fit some utility or function needed by the regime in question. So this logic is often deployed to explain why, say, Egypt and Morocco have multiparty legislatures but Syria and Saudi Arabia do not - there is some function they provide to the former that is not needed in the latter.

The second Plural Regimes school is agnostic or in alignment with these assumptions about an overarching strategic logic of dictatorship, but pays more attention to the specific nature and makeup of the ruling elite and the organization of power itself. To do so, it subdivides non-democracies across explicit category types: military juntas, monarchies, party-dominant regimes, personalist regimes, and electoral authoritarian regimes. These divisions are asserted to be conceptually meaningful, as the nature of power distribution, sectoral elite interests, survival likelihoods, succession strategies, and political institutionalization are believed to vary systematically – at least in a probabilistic sense – across these different types. Here, it is not just generic ‘autocracy’ that acts in a certain way, but rather specific variations on authoritarian rule that do so.

These distinct formats of authoritarian order may be intentionally crafted or chosen, but they also may be the result of regime origination (in revolution or resultant from the characteristics of the victor of violent political strife, for example) as well as the inherited institutional endowment from the regime prior to the given observed one. Additionally, these classifications are ideal-types, and ‘mixed’ or ‘hybrid’ (i.e., conceptually ill-fitting) cases appear often in coding exercises and case-studies. As to be expected, there are significant disputes about which box to place which cases to avoid misclassification and the misidentification of where power sits, and the labels can vary across scholars. This is a more fine-grained approach than the New Authoritarian Institutionalism, but subject to more methods-level controversy due to the conceptual boundaries most commonly used. Terminology thus matters a great deal, as the label given is also assumed to provide some insight into how a regime works.

Here’s a table from Lee Morgenbesser showing how classification types end up fitting together when you apply varying conceptual schemas to an actual set of real-world country-cases within this school of thought:

What both of these dominant frameworks share is an emphasis on authoritarianism as a residual category (i.e. ‘NOT-democracy’) that still is seen to be coherent for theoretical application. They also pay clear attention, albeit at a very high level of abstraction, to organizational form as a relevant marker of how authoritarian political orders are maintained. For the New Authoritarian Institutionalism, this is the matrix of institutions used by the ruler for certain purposes. For the Plural Regimes school, it determines where a case fits in the conceptual schema.

These literatures have developed side-by-side since the late 1990s, although as noted, they often owe core premises to pioneering work on authoritarianism by Samuel P. Huntington and other Cold War era scholarship. Indeed, in applied work, these schools of thought are often intermeshed without theoretical distinction, although there is ultimately a latent tension between ‘all authoritarian regimes share a common strategic logic’ and ‘authoritarian regimes should be conceptually divided across qualitative forms of political order’ that is often elided, even if one allows (or assumes) that they are potentially reconcilable.

Future Directions for Typological Work

This is not the end of the line for studies of political regime, of course. So where do we go from these rich analytical tools? There are several options that are likely to motivate future generations of scholarship. We have broad-based theories of ‘autocracy’ and (now-traditional) schemas of regime distinctions between military, party, personalist, and monarchical types. But this is unlikely to be sufficient, especially as the many different authoritarian regimes of the modern era become increasingly heterogenous and proliferate further. Authoritarianism is clearly ascendant when we scan globe today, and this growth has raised questions about how to put all these puzzle pieces together in a way that is analytically satisfying and useful.

Four potential avenues stand out: a harder look at constitutions and institutional structure, the rediscovery and application of Classical Era insights, more regionally- and temporally-specified frameworks, and deeper dives into how individual institutions really work under authoritarian political orders. And these are only some of many useful avenues of exploration. None are particularly easy, or without their problems, but will certainly bear future analytical fruit.

First, there remains an underserved need to bring back constitutional analysis into comparative authoritarianism studies. That means typologizing constitutional orders and institutional setups and how they interact with authoritarian political order itself at a level below macro-regime characteristics. The older distinctions work at a general level, but there is more variation in how such polities are structured below the surface that is often still uncaptured.

It is a function of the mid-20th century’s historical experience that authoritarian regimes have been so easily placed into single-party/junta/monarchy/personalist organizational boxes. And there is an even stranger quirk of the era to see ‘standard model’ liberal-democratic constitutions, which form the structural core of the growing number of modern ‘electoral authoritarian’ regimes, so dominate the post-Cold War period.

Bouts of authoritarian institutional creativity have occurred in the past and can act as lessons on being attentive to constitutional structures that deviate from these standard paths. The European Interwar Era is an obvious example of the potential for a re-conceptualized understanding of ‘authoritarian constitutionalism’ (the terminology is still underdeveloped here) or corporatism that doesn’t fit well into standard typologies.

The ‘electoral authoritarian’ label we often use suggests a standard setup with a president (or prime minister), a parliament, and a judiciary which looks quite Madisonian, simply denuded of real power. Yet what do we make of the fact that some regimes - such as Russia or Kazakhstan - are readily writing in unelected Security Councils and State Councils into their constitutions? What does it mean that Putin made sure to dress down his most important elites in the Russian Security Council at the start of the war, while has not bothered to appear in parliament? Are these sorts of bodies just more window-dressing facades, or are these constitutional changes meaningful and substantial which tell us something useful about how Russia works? It remains to be seen.

Second, there is plausible theoretical utility in revisiting variations on the old Classical regime distinctions. This is a terminological and conceptual heavy-lift, as scholarship simply does not think this way anymore. Part of the difficulty here is that Classical divisions are explicitly normative - they imply the goals and motivations of the regime under question (‘just,’ or public-benefit rule versus ‘unjust,’ or private-benefit rule).

Yet this sort of approach has had a resurgence in political theory-influenced segments in certain contemporary intellectual circles. Meanwhile, notions of ‘oligarchy’ vs. ‘tyranny’ in particular have (unconnected) echoes in theories of regime cycles, selectorate frameworks, and plenty of political economy models of regime dynamics. There is also an interesting asymmetry here - we are very willing to make normative claims about democracy in terms of its goals (safeguarding liberty or promoting equality, for example), but are understandably loathe to do so for authoritarian regimes and prefer to think of them as uniformly driven by tyrannical and selfish motives.

Although normative classification should be undertaken with care and be very explicit in why this should be done, it remains an untapped vein ready for exploration. Scholarship coming out of non-democratic countries does some of this, as we can see reading Chinese political theory, for example. The globalization of academia will accelerate this tendency, so it’s relevant to understand what’s already going on outside of Western political studies.

Third, building out more limited typologies that apply only to subsets of the authoritarian universe may be particularly fruitful in terms of conceptual granularity. There is a limit to what comparing states with twenty or more years of stable authoritarian rule with the lives of the many short-term regimes found in the empirical world can tell us.

This recognition is certainly already present the literature, but explicitly delineating the universe of cases to which a given conceptualization applies (i.e., explicit application to only ‘long-standing hegemonic electoral authoritarian regimes;’ ‘multiparty constitutional monarchies;’ or ‘legacy communist party-states’ and so on) is sometimes sacrificed for generalizability across the full post-1991 case-set, especially in influential quantitative work.

We may be at the point where using this sort of single-basket approach is more of a theoretical mistake than a boon. For example, a ‘military regime’ category that includes both Myanmar and Sudan in the same conceptual bundle is likely not to be justifiable anymore, especially as the big shock of the Third Wave of Democratization is over and done with. Of course, parsimony and generalizability are important, but there is likely more analytic leverage to be gained from specificity at this stage in the academic literature’s development.

Finally, typologizing political institutions in authoritarian regimes at a higher level of detail is probably warranted. As one small example, in the study of authoritarian parliaments, there remains an overreliance on the category of ‘multiparty parliament’ to mean something specific rather than as a capacious coding box that contains vastly different constellations of party capacity/cooptation, parliamentary institutionalization, and cultures of deference, activism, or obstruction (among many other variations) across cases and time.

Earlier studies made great use of noting differences between parliaments dominated by a single party and those with multiple parties (as well as those without parliaments at all), but a glance at the case-level literature will quickly abjure one from believing that the chaotic factional parliaments of Iran and Kuwait, the constrained party politics of Russia or the antiparty parliament of Belarus, and the organized coalitional-multipartism of Malaysia or Venezuela really fit in the same conceptual set beyond very basic and high-abstraction analytic statements.

For all these reasons, it is important for scholars to reflect on both the richness of current dominant analytic frames in the comparative authoritarianism subfield, as well as the limits to approaches we have focused on for the last thirty years. Building upon these models of authoritarian politics and expanding our analytic eye in multiple directions is very likely the place where the most exciting research agendas will be found in the coming decades.

For Your Reading Interest

Two recent pieces have come out that readers may find to be of interest. The first is a new article of mine at American Purpose, which briefly overviews the small set of internet-based thinkers that are proposing outright authoritarian regimes as a solution to the problems of the United States. This is an ongoing research project, with a full, academic working-paper currently under review (you can find a working paper version here). For the short, pithier version now out, see here, or at the citation below:

“America’s Pro-Authoritarian Theorists,” American Purpose, August 29, https://www.americanpurpose.com/articles/americas-pro-authoritarian-theorists/

A second piece is not my own, but references an article that I published in the policy journal American Affairs this spring. Ross Douthat, the New York Times opinion columnist, has not only read the essay, but favorably cited and summarized it in his Labor Day weekend column last month. The key section is here, which expresses doubt that the rhetoric over imminent ‘democratic backsliding’ in the United States from the current administration is really on-the-level:

You can make a case for Biden refusing these gestures (or a different set pegged to different nonliberal concerns). But that case requires private beliefs that diverge from Biden’s public statements: In particular, a belief that Trumpism is actually too weak to credibly threaten the democratic order and that it’s therefore safe to accept a small risk of, say, a Trump-instigated crisis around the vote count in 2024 if elevating Trumpists increases the odds of liberal victories overall.

For actual evidence supporting such a belief, I recommend reading Julian G. Waller’s essay “Authoritarianism Here?” in the spring 2022 issue of the journal American Affairs. Surveying the literature on so-called democratic backsliding toward authoritarianism around the world, Waller argues that the models almost always involve a popular leader and a dominant party winning sweeping majorities in multiple elections, gaining the ground required to entrench their position and capture cultural institutions, all the while claiming the mantle of practicality and common sense.

…

If Jan. 6 and its aftermath made it easier to imagine a Trumpian G.O.P. precipitating a constitutional crisis, they did not make it more imaginable that it could consolidate power thereafter, in the style of Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan or Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez or any other example. Which in turn makes it relatively safe for the Democratic Party to continue using crisis-of-democracy rhetoric instrumentally, and even tacitly boost Trump within the G.O.P., instead of making the moves toward conciliation and cultural truce that a real crisis would require.

Such is an implication, at least, of Waller’s analysis, and it’s my own longstanding read on Trumpism as well.

That reading may well be too sanguine. But in their hearts, Joe Biden and the leaders of his party clearly think I’m right.

Douthat is coming from a particular partisan position, but he certainly has the primary takeaway from my article right - actually getting to a stable authoritarian regime is much more difficult, and holds to certain general patterns, that are not particularly obvious in the American context. There are plenty of nuances and caveats to this point, of course, but I’m glad to see that my more cautious take on the ‘backsliding’ question (which is what most of the academic literature actually suggests if you read it) is now getting a little bit of notice.

- Julian