Authoritarianism Tomorrow, Part I

What are we missing about the authoritarianism of the future?

Precis/TL;DR: in which we begin a gradual exploration into the question of the ‘authoritarianism of the future.’ We will make no conclusions, but set the stage for further thought down the road. This time we will focus on three strands of contemporary authoritarian theory: Caesarism, tech-futurism, and liberal/progressive technocracy. As always, a list of publications concludes the newsletter.

What We Are All Thinking About

Don’t worry, today’s newsletter is not going to tell you what our collective authoritarian future will look like in the coming decades. We’re not there yet, and I’m still figuring that one out.

We are, however, going to begin thinking aloud here at Political Order(s) on the topic. As my inaugural university course, AUTHORITARIANISM 101, is wending its way to a conclusion, I am about to introduce my students to a select smattering of modern ‘authoritarian theorists.’ A topic we have covered here before, and one which is a side-project of mine.

One thing to keep in mind is that authoritarian theorists are not the same thing as authoritarian regimes, and have in most cases only a partial relation to the phenomenon of going about establishing such a regime (if at all). Plenty of authoritarian regimes have not relied on any grand theoretical backing or justification for the capture of power or, more to the point, the development of one’s own format of political order and institutional (or non-institutional) structures of authority and command.

You really don’t need it! It’s not a necessity. Asserting power can be purely organic, with no foresight. One can, in fact, just be a dictator relying on ‘manual control.’ Or one can simply inherit an old model of governance, like modern-day Arab monarchs or the rare communist regime. No need to theorize anymore, it was done for you a hundred years ago or more.

Or one can also simply inhabit other institutional formats, restructuring authority while leaving the formal governance schema the same (think Turkey or Serbia or Russia wearing the skinsuit of a liberal democratic constitution). And as we get reminded regularly, many cases of autocratization come down to crisis situations gone awry requiring some person, group, or institution to step in or emergencies that are opportunistically used to consolidate power. There’s no plan beyond the immediate-term at all.

Nevertheless, while there is tremendous value in studying the empirical patterns of how power is seized (coup, civil war, internal power-struggle, popular revolution, external imposition, gradual democratic backsliding, executive aggrandizement, etc etc), there is also great value in studying those who advocate for authoritarianism for the sake of the governance model itself.

This complicates any question about ‘authoritarianism tomorrow,’ however. That is, the title of this newsletter. Because exploring the idea of authoritarianism’s future could take multiple forms. It could be that some set of theorists really do gain traction and spur ambitious radicals and activists into action. Karl Marx and the ultimate success of communism several generations later is probably the most famous of these.

The international communist movement of the late 19th century through to the Bolshevik Coup of 1917 was a triumph of authoritarian theory, where true-believer advocates read deeply into ideas like the dictatorship of the proletariat and the inevitable overthrow of bourgeois democracy and structured their visions of the future accordingly (note the particular form of extremely violent and coercive councils of radical theorists that early communism took).

The observed patterns of communist governance were not accidental, but drank deeply from a canon of texts developed by Marx, Engels, Lenin, and others. And the political experimentation within the USSR during the 1920s, mixing theoretical visions of government with the practicalities of war communism, the vagueries of factional power-politics, and the personalization of power around Stalin would ultimately result in one of the more resilient forms of modern authoritarian rule on Earth.

We simply do not get the party-state as it emerged in the real world unless we have Marxism-Leninism paving the way. Now we can also note that communist theory-inspired political action faded over time, as the later history of communism increasingly became a function more of violent external imposition and conquest (although the theorizing still mattered quite a lot as a legitimating motivation for many third-world variants).

But by that time, the theory had already produced a real-world governance model that could simply be copied into a new setting. And that’s what happened.

On the other hand, there are plenty of regimes without a clear theory of substantive, positive authoritarian governance at all. Military juntas often emerge with a generic theory of why they’re intervening (guardianship, survival of the nation or state, anti-communism, anti-colonialism, etc), but not how they would govern or what institutional structures they would build out.

This all makes thinking about the future hard. Will the future of authoritarianism be like the fin de siècle and Interwar periods, with solid (if perhaps fantastical or unworkable) theories of future authoritarian governance motivating political actors, à la the communists, fascists, corporatists, and others?

Or will it be more like the waves of coups in the postcolonial Cold War, where there certainly may be ideology or justifications for rule (here’s a cool new book on African junta militarism), but not ideology telling you what governance itself should look like. It just may not be on offer, and that wouldn’t mean a new fifth or sixth wave of autocratization couldn’t happen. Sometimes things just collapse.

How We Can Tackle The Future

I’m going to be thinking through these questions over the next year or so through this newsletter. My plan is to write a book on the evolution of authoritarianism (and another on authoritarian theory specifically) in the next few years anyway, so might as well start putting digital pen to paper now.

This newsletter issue is Part I of [uncertain X], which means I’m only going to cover the barest skim of my thoughts. But given the above, you can already see there’s at least two (there’s more, but for now there’s two) key moving parts here:

developments in intellectual and ideological projects that argue for substantive authoritarian rule as a solution to one or another problem; and

events or trajectories in politics, society, economics, and so on that result in authoritarian rule, regardless of how it is justified or spelled out.

Reality will inevitably be more complicated, and a prediction from this decade may have little bearing on the course of events two or three decades from now. The Marxist example is again instructive. That the Marxist crowning achievement of a major world power falling to communism in the wake of an industrial world war (and using the governance ideas of the great and terrible authoritarian theorist Vladimir Lenin to format the architecture of power in a truly new way)… occurred in the very last place Marx would have looked is a caution.

Everything interacts and muddles together in the political world to some degree, but that doesn’t mean we can’t make some stylized divisions. So let’s break down a little bit of the ‘state of play’ for these two elements. We’ll do authoritarian theory today, and democratic breakdown in the next series entry.

The Present and Future of Authoritarian Theory

By my count, there are something like three major strands in modern-day authoritarian theory at the level of governance structure (we’ll limit ourselves to that for now). We’re talking alternatives to the standard model ‘liberal-democratic’ constitutional setup that is mostly ubiquitous in the early 21st century. See below for a sidebar on that. That’s our reference category.

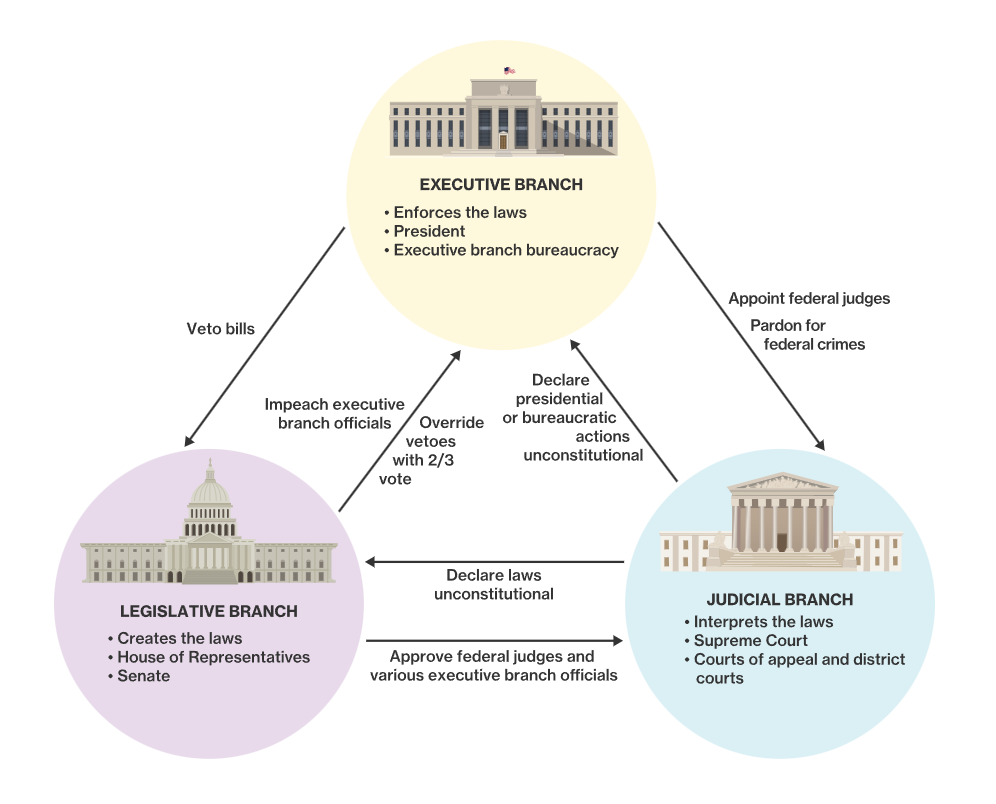

For those who need a tiny refresher, the liberal-democratic constitutional schema is an electoral democracy (“a political regime in which the apex decision-making political offices are chosen through a competitive struggle for the people’s vote by way of regular multiparty elections held under broad suffrage with uncertain outcomes”) with especially strong minoritarian elements (think strong constitutional courts, judicial review, extensive rights guarantees, usually lots of lip-service to separation of powers, plus powerful independent media and NGO complexes). It can be presidentialist or parliamentary, but the core decision-making elites will be chosen through multiparty elections. This variant on democracy is actually really new as far as the judiciary and rights elements go - for most countries only since the latter decades of the Cold War at best (I know, weird!). The United States, as usual, is a massive exception.

There are other regime formats out there - absolute monarchies in the Gulf, legacy communist party-states in China, Vietnam, Laos, and Cuba, the Iranian hybrid theocracy, and a growing cohort of new-generation military juntas primarily in Africa. Almost everyone else uses the liberal-democratic schema, however, and most authoritarian regimes are content to play within those formal constitutional confines.

Onto the three new contenders.

Caesarism

First, the ‘Caesarist’ strain of authoritarian theory. This states, in various ways, that to cut the “Gordian knot” of sclerotic democratic politics, a Man of Destiny (we can wax poetical here, the theorists certainly do) emerges to seize power, brush aside all the detritus and accumulated decay, and reformat governance along personalist lines.

This is a high-brow version of personalist dictatorship. But it’s advocated as such not for emergency purposes or to save the state, but because it’s explicitly better than democracy (for development, for social flourishing, and so on).

There are more casual theorists of Caesarism than there are examples in the world (Charles Haywood is the most disciplined), but I think a case can be made that El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele is probably the man to model. He captured power in a striking way (although notably - not by coup) and refers to himself a “philosopher-king” no less.

Now El Salvador still runs elections and has the formal liberal-democratic constitutional setup, so it’s not a perfect match. Bukele is not actually a pure dictator insofar as that means total personal power. I’m not sure he thinks he needs it (he doesn’t).

Yet the Caesarist vibes are there. And he certainly believes in untrammeled executive power coupled with an ambitious, eccentric, and developmentalist vision for the future as is his cache that he sees as worth emulating. Historical allusions to this model might include Francisco Franco in Spain, António Salazar in Portugal, Józef Piłsudski in Poland, Park Chung Hee in Korea… but there’s many others depending on how you look at it.

Note most of these examples are putschists or coup-leaders, so there’s something quite old about this strain. It’s not ‘new’ to have a strongman (or in the near future, strongwoman) take power. What’s distinct is not that it in vogue again, but that there are strong advocates for it as a lasting solution to the problems of the current era. And that indeed it is viewed as perhaps even necessary given the 21st century’s tendency towards decision paralysis, a problem we will bring up again below.

Tech-Futurism

The second theoretical archetype of the era is a kind of futurist, tech-reactionary governance. The purest and most concrete example is ‘neoreaction,’ which is the label given to the ideological project of America’s foremost authoritarian theorist, Curtis Yarvin. Frankly, Yarvin has become much more of a generic Caesarist in recent years (just as his star has greatly risen in mainstream public prominence, funnily enough).

But his old ideas from the late 2000s are some of the more well-baked (perhaps up to one-third baked) entries in the genre of new, Silicon Valley style thinking on authoritarian rule. His main claim then was an argument in favor of a CEO-monarchy, overseen by a blockchain oversight architecture, which would exist in a patchwork of free-to-exit networked city-states which would maximize contented order and minimize intrasocial conflict by allowing you to choose which micro-authoritarian regime you’d like to live in.

Singapore is the model for the city-state bit, Neal Stephenson’s sci-fi writing inspired some of the libertarianesque elements of exit, and Hans-Hermann Hoppe provided the monarchy idea. He’s mostly cast this aside in favor of speaking more generally about monarchy and FDR, for the time being. Which is probably because the blockchain stuff is very silly, whereas Caesarism has a great empirical track record.

Still, Yarvin’s older authoritarian vision is one of many percolating in Silicon Valley, however. There’s lots of interest in constitutions with ‘internet governance’ included, or billionaires talking about ‘exit’ and “network states,” or looking at “decentralized autonomous organizations” (see Yarvin on DAOs, and then see a normie political scientist with a shockingly similar interest in “optimized governance”).

Hey, I myself even made the hypothetical case for authoritarian governance in long-term extraterrestrial space settlements (a sci-fi inflected interest of mine I’ve expressed here too). Although my father disagrees on the settlement viability bit. Elon Musk curiously believes we can have democracy on Mars, but I think he’s wrong. So really there’s an entry point here for everyone, even small-d national democrats like me.

And more seriously, authoritarian futurist aesthetics have recently found a home in the UAE, an actual “high-technology” monarchy (with an actual semi-slave labor caste). Futurist tech-authoritarianism is a hot-topic, but we happen to be only in the middle of Version 2.0 of articulating these ideas out loud, so it’s early days yet. China sometimes fits into this camp, but it’s such a legacy party-state that it can only kind of count. We’ll have to make some distinctions later on that one. But hold that thought.

Liberal/Progressive Technocracy

The third trend in modern authoritarian theory is technocratic and ideologically liberal or left-progressive in most cases, certainly relative to the obvious right-wing slants of the first two. This is the idea that democracy itself is too vulnerable to populism, too prone to demagoguery, too economically incontinent, and/or too indecisive in the face of perceived existential threats like climate change or pandemics.

We have articles in the American Journal of Political Science promoting climate change-induced emergency rule, we have cancelled elections in Romania and jail terms for populist opposition in France, we have leftist academic critics arguing the entire European Union is a project of “authoritarian liberalism,” and so on. It is not hard to find someone make the case that “the world is burning” with the implication that, well, something must be done.

Empirically, this sort of technocratic authoritarianism has taken the form of unaccountable supranational bureaucratic oversight or de facto tutelary judicial rule. It’s rare to see it fully spelled out so far, but recourse to elitist oversight in various institutional forms has assuredly gotten more common in the last decade. Even The Economist says so! You can find a partial critique of technocracy from the left here, although I’ll admit the solutions presented are dumb.

The draw of technocratic authoritarianism is consistently underplayed in media and academia because those that think in these terms don’t consider them authoritarian at all. It’s not censorship, it’s countering misinformation. It’s not political coercion against the opposition, it’s defending democracy (or in academic terms “militant democracy”).

And proponents have reasons to think this! There’s no reason per se one must let anti-system malcontents run free in order to stay a democratic political regime. One is allowed to identify real threats to a given political order.

But technocratic thinking (especially in its emergency forms or as supranational interventions) invites a worldview not all so different from the coup-plotter: my coercive actions against elected officials or popular views are justified to save the state. And one may be correct! You’ll never get me to say that a political regime must come before someone’s life or the survival of the nation. But at some point, we shouldn’t call whatever that is a democracy. More on that another time.

Anyway, those are my three categories to watch right now: Caesarism, tech-futurism, and technocracy. By no means will these be the dominant strands of authoritarian theory in the future. But they are the ones we have right now, with real governance paradigms and real people writing and producing content about them and real audiences listening.

Now, if you have other examples or an entire new strain of thought that I’ve missed with these above broad characterizations, do let me know! We’re thinking out loud here. And I swear I take comments (here, over email, wherever) happily, especially if they are nice and interesting.

Next time, we’ll talk about the other side to the future coin. No fleshed out, substantive, and intentional authoritarian theory itself. Just general conditions that lead to the collapse of democracy or a new wave of new kinds of authoritarian rule - regardless of whether anyone planned it, or thought it through…

Further Reading

There are a few new reading updates, I’m listing them here to peruse at your pleasure. I’m also expecting a few articles to come out between now and June (??) to share as well.

First, I have a new book review out on Jerome Copulsky’s American Heretics: Religious Adversaries to Liberal Order (Yale University Press) published at FUSION. I argue that Copulsky’s work, which is a refreshingly neutral look at religious-inspired critics of America’s political and social order across the centuries, is also a tale of American nationhood and its challenges. You can find “National Heresies” here.

Second, please check out my AUTHORITARIANISM 101 Midterm Update essay from a few weeks ago. It’s good and you’re probably interested:

Third, I have an article out at West Point’s Modern War Institute on the collapse of the Syrian regime and what says, and more importantly doesn’t tell us, about authoritarian regime durability and threats to survival. Read “Bashar al-Assad and the Oversimplified Myth of Autocracies' Inherent Fragility” here.

Fourth, we have a new major report out on the Russia-Iran relationship from my team at CNA. In general, the relationship is getting better - and we tell you exactly where. I was the lead author and analyst on this report, although it was a great collaboration with several excellent colleagues. Read The Evolving Russia-Iran Relationship: Political, Military, and Economic Dimensions of an Improving Partnership, here.

Fifth, we have another major report on civil-military relations in wartime Russia. This one has Prigozhin in it, and we snuck in an original conceptual framework for the study of civil-military dynamics too. This one I’m lead author on, with vital quantitative support from my colleague Cornell Overfield. Read Wartime Russian Civil-Military Relations: Dimensions, Tensions, and Disruptions here.

An Outside Reading Corner

To be perfectly honest, I’m behind on my reading goals. So read our book instead. I am still waiting for one of you to review it (kindly, wonderfully, graciously) on Amazon or your own bespoke writing platforms. :)

That’s all from me for now!

- Julian

Very good from the non PS’s perspective. It was readily understandable. It is very tempting to comment on the weakness of the first as reheated models of authoritarian rule. Different wrapper but it will taste the same and the current president seems to be delivering lessons on it’s effectiveness. I could see the second works for small sovereign states but couldn’t see this taking hold in France! the third is very thought provoking personally. As a European these are very real issues, as you highlight. I await the second lesson which l will hope will neither induce panic and the need to book the first available ticket to Mars.

I would love to have seen Konstantin Pat's 1938 Estonian Constitution actually be put in effect for an extended period of time.

It might've provided a model for nations which, for various structural reasons cannot do democracy effectively, but a 'formalist, semi-democratic regime' like that would have provided it with the 'rule of law'.

Syria under Hafez Al-Assad I guess was kind of similar. That was a 'formalist regime'.